Produced by the Institute for Tribal Government at Portland State University in 2004, the landmark “Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times” interview series presents the oral histories of contemporary leaders who have played instrumental roles in Native nations' struggles for sovereignty, self-determination, and treaty rights. The leadership themes presented in these unique videos provide a rich resource that can be used by present and future generations of Native nations, students in Native American studies programs, and other interested groups.

In this interview, conducted in July 2002, Native American Rights Fund (NARF) co-founder and Executive Director John Echohawk shares his journey as a leader in Indian Country. A powerful voice in cases supporting Indian rights throughout the U.S., he has won numerous awards for his achievements.

This video resource is featured on the Indigenous Governance Database with the permission of the Institute for Tribal Government.

Additional Information

Echohawk, John. "Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times" (interview series). Institute for Tribal Government, Portland State University. Portland, Oregon. July 2002. Interview.

Transcript

Kathryn Harrison:

"Hello. My name is Kathryn Harrison. I am presently the Chairperson of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon. I have served on my council for 21 years. Tribal leaders have influenced the history of this country since time immemorial. Their stories have been handed down from generation to generation. Their teaching is alive today in our great contemporary tribal leaders whose stories told in this series are an inspiration to all Americans both tribal and non-tribal. In particular it is my hope that Indian youth everywhere will recognize the contributions and sacrifices made by these great tribal leaders."

[Native music]

Narrator:

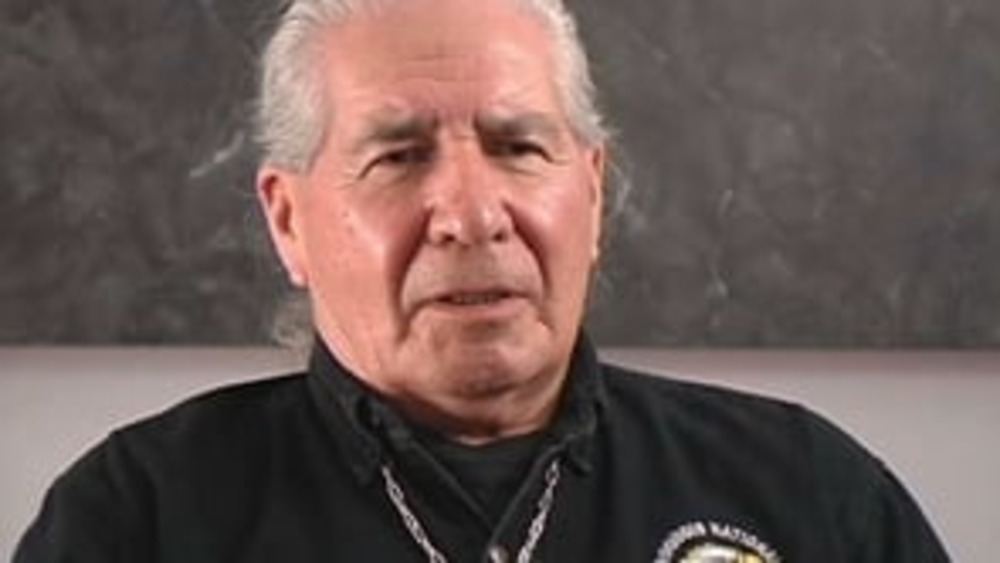

"John Echohawk, Executive Director of the Native American Rights Fund, NARF, today oversees multiple lawsuits on behalf of Native tribes in a more than 30 year career of correcting century's old injustices through the legal system. NARF, a nonprofit organization located in a rehabilitated fraternity house in Boulder, Colorado, provides legal representation and technical assistance to Indian tribes, organizations and individuals nationwide, a constituency that has historically lacked access to the justice system. Echohawk has been with NARF since 1970 and served as Executive Director since 1977. Born and raised in New Mexico, John Echohawk is a member of the Pawnee Tribe of Oklahoma. From a family that emphasized education, he is one of three siblings out of six that grew up to be lawyers. After attending Farmington High School he received his BA from the University of New Mexico at Albuquerque and was the first graduate of the University of New Mexico's special program to train Indian lawyers. He was a founding member of the American Indian Law Students Association while in law school. His years of study coincided with a time of national tumult and social change, when the inequitable treatment of African Americans and other minorities including Native Americans was coming into vivid focus. His studies also coincided with a crucial period in federal Indian relations when the federal government had been systematically dismantling reservations through legislation. The Ford Foundation which had also assisted the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People issued a grant to California Legal Services for an Indian Legal Defense Fund. From this the Native American Rights Fund was formed. The organization was then moved to Colorado to be more central to the tribes it represents. In his years with NARF John Echohawk has worked with tribes throughout the lower 48 and Alaska on crucial and often contentious issues of natural resources, tribal sovereignty, human rights and ancestral burial grounds. His rule of thumb if, "˜Never give up.' Twice recognized by the National Law Journal as one of the 100 most influential lawyers in the United States, Echohawk has opened doors and forged many alliances in his work for Native tribes. One of the boards on which he serves is the National Resources Defense Council. He believes that Native Americans and environmentalists ought to be natural allies. He also serves on the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy and the National Center for American Indian Enterprise Development. In 1995 he was appointed by President Clinton to serve on the Western Water Policy Review Advisory Commission. One of the most sought after experts on Indian issues, John Echohawk has received numerous awards over the years including The Spirit of Excellence Award from the American Bar Association. On behalf of the Native American Rights Fund he accepted the seventh Carter-Menil Human Rights Prize in 1992. Echohawk has been married almost 40 years to his wife Kathryn whom he met in Farmington where the two grew up. He has one son, a scientist at the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico and a daughter who works at the American Indian College Fund in Denver helping Indian colleges grow. John and Kathryn Echohawk also enjoy spending time with their grandchildren. The Institute for Tribal Government interviewed John Echohawk in Portland, Oregon, July, 2002."

The war on poverty initiative and the beginning of the Indian Law Program

John Echohawk:

"I was one of the participants in the first Indian Law Program started by the federal government to develop some Indian attorneys that had been realized by the federal government at that time through their Office of Economic Opportunity, the War on Poverty that occurred during the 1960s, that there were only a handful of Native American attorneys across the whole country and that perhaps one of the best strategies to try to fight poverty in Indian communities was to get some Indians who were professionals like doctors and like lawyers. I checked with the University of New Mexico Law School for scholarship assistance and they told me that they had just contracted with the federal government to start this Indian Law scholarship program so I was just in the right place at the right time and accepted one of these scholarships and became part of the first class of Indian law students to start studying law under this new federal initiative."

The impact of the social movements of the 1960s on Echohawk's life work

John Echohawk:

"The Civil Rights Movement was something that I was able to put into context by going to law school. Of course I learned about the legal process and how that system works and basically I found that through the use of law in litigation that people could have their rights recognized and enforced even though they were politically unpopular and that's what was happening during the Civil Rights Movement. The courts were doing cases that provided equal protection and equal treatment for African Americans in this country for the first time and even though that was not politically popular this is what was required by the laws of this country if there was to be equal treatment of all people in this country. And so I saw how that happened through the use of the litigation process and when we started thinking about how that impacted Native American people we saw that we needed to utilize that same strategy. There had never been Indian law taught in the law schools and so the professors started pulling together the materials relating to Indian treaties and federal statutes relating to law and the treatises that had been done on Indian law and so the first time there was a body of materials that could be studied about Indian law. And when us Indian law students started reading that we saw that our tribes had substantial rights in the treaties and in the federal laws that were really going unenforced and the reason that was happening is because this legal process requires you to have attorneys to assert and protect your rights and if you don't have attorneys then it doesn't matter what it says in the treaties and the statutes. You don't have any rights. The tribes did not have lawyers cause they didn't have any money. They were poor and so we knew that what needed to be done was to get lawyers for tribes to assert these rights that tribes had. And that's when we decided that we needed to start the Native American Rights Fund, a nonprofit organization that would raise funds, hire lawyers expert in Indian law and make them available to the tribes around the country. We knew this would be something that would be beneficial cause we had seen at the same time we were in law school the start of civil legal services programs funded by the federal government being put out into poor communities around the country so that poor people could have lawyers. And some of these programs were started on Indian reservations. Of course the federal government didn't have enough money to put legal services lawyers on all the reservations so it was really present on only a few of the reservations but where they were active they were able to do many things in terms of enforcing Indian laws for the benefit of Indians. So we saw the formation of something like the Native American Rights Fund as being able to take the provision of legal services to tribes on a national basis and help many more people."

Native American Rights Fund attorneys modeled their efforts on the NAACP in building up their organization

John Echohawk:

"Well, again, we learned from the Civil Rights Movement how that was done. We looked at where the lawyers for the African Americans was coming from that brought the Civil Rights litigation and their counsel most of the time was the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund and that was a nonprofit organization that raised money and then hired lawyers to represent these African Americans in these important Civil Rights cases. And the funding, primary funding for that NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund came from the Ford Foundation in New York City. So we made contacts with the Ford Foundation in New York City and started discussions about forming a national legal defense fund for Native Americans and they were interested and ended up making a grant then in 1970 to start the Native American Rights Fund in that same model as the Civil Rights organization for the Blacks, they provided the counsel. We began as part of the California Indian Legal Services, one of these federally funded Indian legal services programs I talked about and we were a project of that organization for a year until we were able to incorporate separately and establish our national headquarters in Boulder, Colorado."

The priorities of the growing Native American Rights Fund

John Echohawk:

"Well, we started with the three lawyer program but we quickly got overwhelmed by requests for assistance from throughout Indian Country to help and with that we sought additional funding that came through from different foundations and the federal government through this legal services program and we were able to expand in a very short time to a staff of about 15 attorneys and we were able to do a wide variety of cases under the direction of an all-Indian Board of Directors. That established us as priorities cases relating to the protection of our tribal sovereignty, our existence as tribal governments, secondly the protection of our natural resources, our land, our water rights, our hunting and fishing rights and thirdly protection of our human rights, our rights to cultural and religious freedom and expression."

The historic Menominee termination case

John Echohawk:

"And one of the first cases that we undertook was to try to reverse the federal Indian policy at that time which was one of termination of tribes. The federal government had decided that the best policy for tribes was to quit being Indians and to have their tribal governments terminated and to be forced to assimilate into the larger non-Indian society. And this was the existing federal policy at the time when the organization was founded in 1970. So to do away with that termination policy we undertook to represent the Menominee Nation of Wisconsin, one of these tribes that had been terminated starting with an act of Congress in 1954. And of course at the time the Congress told the Menominee people, 'this would be good for you, this is going to help you,' and of course what happened as a result of that is exactly the opposite. It nearly destroyed the Menominee Nation. They lost a lot of their land through that process, many of their people ended up instead of being productively employed ended up on the unemployment rolls and it just devastated that community. So we helped the Menominee Nation go to Congress and develop a bill that would restore the Menominee Nation's tribal government and tribal status and eliminate this termination of the tribe. We asked the Congress to basically look at the record and admit that this termination policy was wrong and to change it and to their credit Congress did that. They said, 'Yeah, this was clearly a mistake, this was not good for the Indian people so we need to change that.' They restored the tribe and that set up restoration of all the other tribes that had been terminated during that same period and of course that's happened over the last 30 years since that first Menominee restoration in 1973."

Changing federal policies toward sovereign Indian governments

John Echohawk:

"Since 1787 when this nation came into being and adopted the Constitution, what's the relationship between tribal nations that of course pre-existed the start of the United States government and the United States itself and of course in the Constitution this nation recognizes that tribal governments have sovereign status, that they are governments like state governments and like foreign governments and that there's this government to government relationship between the United States and between the tribal nations that's governed by the Congress. For a long time that was done by treaties and then later it was done by federal statute. But essentially it's a relationship between sovereigns, between governments and from time to time U.S. policy in dealing with tribes has been rather one sided and they haven't listened to what the tribes have wanted to do and they have basically forced their own version of what they think is good for Indian people on Indian people through the passage of these laws. And one of them was this termination policy that reflected really the paternalism of White America about what was good for our people without really even asking them and they were basically saying, 'You're better off not being an Indian,' and that was the crux of the termination policy but again they never asked the Indians about that. And when they did, the Indians said, 'We want to continue to be Indians, we want to continue to exist as tribal people, we want to continue to govern ourselves through our tribal governments and exercise a sovereignty that we've had since time immemorial and control our own affairs and continue the existence of our tribal nations.' And of course that's what's become the policy now that the termination philosophy was rejected and this Indian self-determination policy accepted by the federal government. Of course that's now been in place about 30 years and I think it's helped our tribes tremendously as we've finally been able to put a stop to this termination policy and start governing ourselves once again."

Finding allies in Congress for a reversal of termination

John Echohawk:

"We had gone to the Congress looking for representatives in the Senate and in the House who would be supportive of this tribal position. And it's been so long ago I can't remember all of the players but there were some champions there that came through for us. I think on the Senate side Senator Abourezk from South Dakota was very helpful in particular and on the House side Congressman Morris Udall from Arizona was very supportive as well. But Indian people generally have been able to rely on champions like that beginning in the '70s, into the '80s and through the '90s and here into the new millennium too to basically stand up and fight for tribes and support their rights under new laws and the Constitution of this country."

The unique situation and challenges of Alaskan villages and tribes

John Echohawk:

"Well, I mentioned this termination policy that had been in place. The version of that for the Alaska tribes was this Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act that was passed by the Congress in 1971. The tribes in Alaska had never been able to get the attention of the federal government and to make treaties with the federal government to have their claims to tribal sovereignty and their aboriginal title to their lands and waters and hunting and fishing rights recognized by the federal government. They had just been in limbo all this time clear up until 1971. But the Natives finally got some leverage with the discovery of oil on the north slope of Alaska and they wanted to put the pipeline down through the middle of Alaska and transport the oil that way. Well, the Natives saw a way to get the attention of the federal government by filing lawsuits to block the pipeline until such time as their claims to that land were settled. That was their aboriginal land and the Congress refused to deal with that issue. But when the Natives threatened to stop the pipeline through this lengthy litigation then Congress finally was forced to deal with land claims of tribes in Alaska and that resulted in the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971. The tribes came away with recognition of title to land of about 44 million acres, about 10 percent of Alaska and about $1 billion in compensation for their other claims. But the strange part of the legislation was that this land and money did not go directly to the tribes. Congress again in the final stages of this termination period in an experiment set up Native corporations and put the land and the money into Native corporations and the Natives became shareholders of corporations. And so their land and money was held in a different way than tribes in the lower 48 where it's held by tribes. What that left open then was whether tribal governments had jurisdiction over that land in the same way that tribes have jurisdiction over their land in the lower 48. Is that Indian Country over which tribal governments can assert jurisdiction since it's not owned by the tribe, it's owned by these corporations that are owned by the individual tribal members? That was the question presented in this case brought by the Native village of Venetie where they sought to generate some revenues to support their tribal government by imposing taxes on people who lived and worked on their land and some of those people were non-Indians and they challenged the authority of the Venetie tribal government to tax them saying they didn't have authority to do that and the question was, is this Indian Country just like in the lower 48 and even though we won the case in the lower courts the Supreme Court reversed our victories and held that there is no Indian Country jurisdiction in Alaska, that the fact that these lands are held by Native corporations and not tribal governments makes a difference and that we have no tribal authority over our lands in Alaska because of this corporate status."

The impact of the Supreme Court reversal

John Echohawk:

"Well, what it means is that the tribes in Alaska don't have the same authority over their lands as the tries in the lower 48 and that means they're under state jurisdiction and with tribal governments being a distinct minority in Alaska they have difficulty controlling what happens in their own communities on their own lands and this is something that they want to correct and they've started discussions with the State of Alaska and with the Alaska delegation about this and they've started to make some inroads in getting the authority of Alaska tribal governments over their lands addressed. So even though the case was lost it started a discussion and a dialogue up there that started to result in change where tribal governments in Alaska are starting to be recognized as having the same powers and authorities over their lands as the tribes in the lower 48 so again it's another come back from this termination policy that had plagued us for so long."

Some of NARF's cases have roots deep in the past: the Trust Funds case

John Echohawk:

"The Trust Fund's case described as this case brought by Elouise Cobell as the lead plaintiff in the lawsuit is a case that had really been out there for a long, long time that we were aware was out there for a long, long time but we were hoping wouldn't really ever have to be brought. Of course we had questions whether we would ever have the resources to bring it since it is the largest case that we've ever gotten involved in. But it starts with the fact that Indian lands are held in trust for Indians by the federal government. In that sense it's different from ownership of land that most people are familiar with in the United States. Generally speaking the title to tribal lands and individual Indian lands on reservations is not held by the tribe or by the individual Indians, it is held by the United States but it's held in trust for the benefit of the tribes or the individual Indians and that makes the federal government a trustee. In the beginning the land started out of course as land owned in common by the tribes. Initially that was the way that the federal government and the tribes established their relationship. But beginning in the 1880s with the Indian Allotment Act, Congress adopted a new policy part of this assimilation mentality that they had trying to force Indians to assimilate into the mainstream. They took some of this tribal land and divided it up and gave some of it to individual Indians, members of the tribe. And so individual Indians on some reservations for the first time got individual ownership of land but that land was still held in trust by the federal government for them. And of course as trustee then, like any bank, well, what that means then is the trustee when the land's to be leased for timber development or oil and gas development, the trustee signs the leases, collects the money and keeps it in an account for the beneficiary, the individual Indian. So the United States as our trustee became our banker and they were supposed to do all this for individual Indians who got these individual allotments beginning in the 1880s on many reservations across this country. Well, the federal government over all that time has not made a very good banker. They didn't keep track of all of these records and all these accounts and all of this money on all of these leases. This became evident pretty early. Beginning in the early 1900s there were starting to be reports of how the government was not managing these individual Indian money accounts for all these individual Indians that had these leases that the federal government was administering. Complaints were made to the Congress and to the Bureau of Indian Affairs and unfortunately nothing was done about them and even though these complaints would regularly be raised in the Congress and in the administrations all throughout the 1900s nothing was ever done about it. The latest effort was led by Elouise Cobell, the lead plaintiff in this lawsuit that we're talking about. She got an act of Congress passed together with many other people in 1994 called the Trust Reform Act and what this did was put a special trustee into the Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs to clean up this mismanagement of the individual Indian trust funds. Well, it turned out to be politics as usual because promptly after 1994 the administration never asked for any money to implement this law and Congress didn't give them any, didn't provide any itself so everybody passed this law and kind of promptly forgot about it so it was business as usual. So we made a determination at that time that the Indian trust funds mess was never going to be resolved politically by the Congress and by the administrations, that we had to enlist the aid of the federal courts to do that and to enforce this clear federal trust responsibility and make them account for all of this money for these individual Indians that everybody knew had been mismanaged but nobody was ever going to fix it. But by enlisting the aid of the court, the court could enforce the trust responsibility and make the Interior Department reform the trust and do an accounting. That's what we asked for in the lawsuit that was then brought in 1996. The courts have responded magnificently. They've read the law, they see that the Congress has accepted this role as trustee through the enactment of all of these laws relating to our people that the federal government has a clear responsibility that has to be carried out by the Interior Department and the Department owes all of these individual Indian money account holders now estimated to be as 500,000 an accounting of their funds going back to the 1880s. And the federal government has resisted the efforts of the individual Indian money account holders at every step of the way since 1996 but again the courts have ruled in favor of the Indians at every turn and we're still waiting for this accounting of funds."

The conditions of Indian tribes and the obligations of the federal government

John Echohawk:

"Even though the federal government has taken on substantial obligations to tribes through the treaties and through the laws they have never lived up to their responsibilities. That's why we've got such poor social and economic conditions on Indian reservations. We're at the bottom of the ladder on virtually everything. We've been able to make substantial inroads into that in the last 30 years during this self-determination policy when we've taken more of the control ourselves but still we have a lot of catch up to do. There's not only neglect in the management of the trust funds of individuals and of tribes but in education, in health, in roads and infrastructure on Indian reservations, jobs, income, whatever it is we're at the bottom of those statistics and much of it is due to the fact the federal government just has not provided the assistance and support that they promised the tribes through the treaties and through the statutes. Much of that comes down to the appropriation process where Congress appropriates money to carry out the treaties and its responsibilities and even though all of our tribes have worked very hard to get the necessary appropriations to implement those laws we just haven't been able to get the kind of funding that we need and that's why tribes through the exercise of their authority as tribal governments have worked so hard in developing their economies and prioritized economic development because unless we're able to provide for ourselves it's unlikely that the conditions on our reservations are going to change very much cause the Congress, the United States of America just has not done a good job of fulfilling its responsibilities to Native people."

The public is informed about trust funds mismanagement but the problem continues

John Echohawk:

"I think this case has gotten a lot of widespread publicity across the country. We've worked very hard at doing that hoping to be able to force the federal government to enter into negotiations with us and settle this case but all of that exposure has really not worked in the sense that the federal government continues to resist, continues to deny that it has any responsibility for the mismanagement of these funds and continues to resist us at every turn. But thankfully we have the support of the federal courts and I think it's one of the most difficult cases they've ever had trying to force the executive branch of government to do what they're supposed to do, which is to follow the law. And it's gotten so bad now that we've asked the court to hold federal officials responsible for the trust reform in contempt of court for not complying with court orders and to put these officials in jail and assess fines against them personally. And we've also asked the court to basically take these responsibilities away from the Department of the Interior on a temporary basis and to have the court appoint a receiver that would carry out the trust reform under the jurisdiction of the court until such time as we got it fixed and then got the Interior Department people trained in how to administer that trust and then turned it back over to them once they demonstrated they're able to do it properly. These are extreme measures but again they're prompted by the fact that there has been extreme reluctance on the part of the executive branch to carry out the law of this country."

What the injustice over trust funds has meant for tribal people

John Echohawk:

"Well, we think as a result of the shoddy mismanagement of these Indian trust accounts that our people over the generations have really been defrauded and have lost a lot of the money that was due them under these leases that were being managed by the federal government. And of course interest is due on all of that money that we should have had too. So as Elouise Cobell likes to talk about, she thinks a lot of the wealth that our people had in these lands has been dissipated, lost by this mismanagement. And if we had had that money the conditions of our people over the last few generations would have been better. But that should be made up by this accounting when we I think basically determine that there have been billions of dollars that have been lost through that process and together with interest there are billions that are owed to these account holders and that's the part of the case that we're pressing forward on right now in 2002. The next phase of the case after we get this trust reform effort underway to stop the bleeding to fix the system now and that's to get to the accounting part of the case and to have a trial on that issue and establish that there should be billions of dollars in these accounts and the accounts should be restated to reflect that. Like I say, we didn't expect it to go on as long as it has. We thought the federal government would use this as an opportunity to settle what's clearly been recognized a long time as a mess."

How John Echohawk has maintained the strength of his commitments for more than three decades

John Echohawk:

"As a lawyer with tribal clients I take those responsibilities seriously and I represent my clients to the best of my ability. It's very interesting work, very rewarding work. We haven't been able to win all of these cases but we've won a substantial number of them and I've seen where that's made a difference in our Indian communities as we've talked about the change in Indian policy from termination to self-determination here over the last 30 years and the gradual improvement of social and economic conditions amongst our tribes even though we've got a long way to go and we're still pretty bad off, it's a lot better than it used to be. So it's been rewarding. I see the kind of work that I'm doing as something that really falls to each generation of Native people in this country. Reading the history of our people and all of the legal and political struggles they've been through since the founding of the nation in 1787 and even before then, each generation of Native people has had these issues that they've had to deal with. What's their relationship with the United States and what kind of conditions are they going to be living under today and what power do they have as tribal nations to impact that? And these are issues again that past generations have had, that our generation now has and the future generation of Native American people are going to have as well. I think that's why it's good to have programs like the Institute for Tribal Government do these kinds of projects where we can educate younger Indian people and Americans across the board about the history of tribes, the current issues and the future issues that are coming along that impact tribes and to get the younger generations of Native and non-Native people ready to deal with these issues because they will go on. The status of Native American people in this country has always been an issue in this country and it will always continue to be an issue in this country."

The preservation of Native religions and culture

John Echohawk:

"Well, our people are not only governments, nations but we're also people with different cultures and religions and that's I think the most important thing to our people is to continue to live the way that we were brought up by our mothers and fathers and our ancestors before that and to be able to follow the traditions and cultures and religions of our people and having the sovereign status as nations, as governments allows us to do that, to be able to make decisions that protect our tribes, our ways of life, our cultures and our religions and traditions. So along with protecting this governmental status we want to make sure that we can protect our culture and religious rights as much as possible, that's why this is one of the priorities that we've worked on at the Native American Rights Fund over this time. One of the areas we worked in quite a bit has been in the religious freedom of Native Americans. So many people in this country don't understand that many tribes have their own religions and in our view these religions are entitled to the same protection in this country as other religions but so many people just do not understand first of all that we have our own religions and then too they have trouble understanding that these religions ought to be accepted and protected on the same basis as other religions in this country so we've got a lot of work on that concept. The Congress passed the Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1978 which was a declaration of policy intended to help all Americans understand that tribes do have their own religions and they're entitled the same respect as other religions but actually getting that implemented across the board has been difficult and there's been many cases on that. We've been involved in a number of them and it's still a very difficult and contentious issue."

Protecting Native sites, the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act

John Echohawk:

"The whole country at one time basically being Indian Country we have inhabited the whole area since the beginning of time and we have burial sites all over this country, not just on the lands that we have left called reservations but on all of these lands and as this development occurs they are unearthing many of our tribal burial grounds and for so long under this termination policy most of America thought that tribes were extinct or disappearing and so when they did unearth our ancestors they hauled them away as if they owned them and that we as tribes didn't have any control over the remains of our ancestors. And we finally got Congress to pass a law in 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act that stopped that practice and recognized that our tribes own and control the remains of our ancestors and their burial goods and that they can't be taken away by other interests and that they do belong to us. So we've been able to stop that process and start reversing it by repatriating the bodies of our ancestors they've taken to the museums and all of the burial goods that they've confiscated and to return those to our people. And that has been a significant development."

Indian tribes and environmental issues

John Echohawk:

"The environmental movement really started about the same time as the Indian self determination movement in 1970. The environmental movement resulted primarily in a number of federal environmental laws that protect the environment across the country by setting minimal environmental standards that are to be met to stop and manage the pollution that has occurred. Under these federal laws most of them are carried out by states that contract with the federal government and then follow these federal environmental standards and implement them in the states. Well, of course as we've established in this Indian self determination era going back to the treaties, the jurisdiction on the Indian lands is the combination of tribal law and federal law based on this federal tribal relationship and state law does not apply on our lands unless that's been made applicable by a treaty or an act of Congress. These environmental laws did not give the states jurisdiction to enforce these environmental laws on our lands. That's still a prerogative of the tribal governments so what we've been doing as part of this Indian self determination and environmental movement is having the tribes develop their own environmental laws under the federal environmental statutes to take care of the environment on Indian lands. The environmental organizations that have been involved in overseeing this whole process like many Americans have not really been familiar with tribes and tribal governments and tribal authority so it's been important to reach out to them and explain to them why on Indian lands these environmental laws are implemented and controlled by the tribal governments instead of the state governments. I think they've become learners like American people generally about the existence of tribes and tribal governments and tribal authority and tribal nations and have been supportive of tribes regulating the environment on tribal lands. I've been one of several tribal people who have been involved in outreach to the environmental community about these issues and I've found it very interesting to see their reaction which is generally positive after they learn how all of this fits together under this legal system we have. But at the same time I've benefited from working with environmentalists to learn more about the environmental threats that do exist around the world and in this country and on our own lands too and be able to work with them to address these environmental problems that we have on our lands."

Individuals and foundations nationwide who believe in the protection of Native rights support NARF

John Echohawk:

"We've been able to establish a network of 40,000 individual contributors across the country that help us raise funds every year. In recent years too we've also seen tribes because of the increase in the ability they have to generate funds to help their people and their social and economic development be able to contribute part of that back to organizations like the Native American Rights Fund that have helped them do that so we've seen tribal contributions grow in recent years. I think even though we've been able to sustain the Native American Rights Fund at this level of around 15 attorneys for this 32 year period that we've been around, we haven't really despaired too much because the major development that's occurred during that time has been the number of tribes who are now able to afford their own attorneys. Thirty-two years ago there were only a handful of tribes that could do that but these days because of the progress that tribes have made most of the tribes today have their own attorneys. Maybe not as many as they need but they at least have some legal assistance available to them and that's helped them tremendously because I think tribes have learned so much of what's involved in protecting your tribes is dealing with the legal and political systems in this country and that for better or worse requires the use of lawyers. And our tribes now have a lot of legal counsel today, many, many more than they had when we started back in 1970 when together with Indian Legal Services we were about the only legal counsel available to tribes."

How to deal with setbacks

John Echohawk:

"Well, you try to figure out what you can learn from that and then how you can move forward with basically the same issues and try to change the outcome. In other words, never give up."

Never giving up, using the cases to educate the public

John Echohawk:

"I think really a process of starting with the United States Constitution, which is to say you talk about the American system of government and how tribes fit into that system. Even though that's really very basic so many Americans don't really understand that. It should be taught in our public schools and in our civics courses but unfortunately it's not addressed. And so we end up with the vast majority of American people not having any idea about the existence of tribal governments in this country today and the fact that it's based on the Constitution and treaties of this country. So it's a process that me and other Native Americans are involved in all of the time, it's a continual education process. It's particularly critical at the congressional level when these issues end up before Congress cause we end up with so many of our elected representatives really not only in Congress but the state level too not understanding the basics of American government that includes tribal governments. So we talk amongst ourselves about having to do an Indian 101 course like in college when you talk with federal and state leaders cause so many of them don't have any idea about our status as governments."

Educating around misconceptions about Indian issues, especially gaming

John Echohawk:

"Well, you have to talk about the Constitution and the treaties and the fact that tribes are governments like the states and like the federal government and that tribes like other governments have a need to raise revenue to provide services and just like the state governments do who operate games of all kinds to generate revenues, tribal governments are able to do that too under tribal law and that even though tribes have that option not all of them exercise that, that not all of the tribes are involved in gaming. There are 557 recognized tribes around this country. Less than half of them engage in gaming. Of the ones that do engage in gaming only a handful make a lot of money off of it because of their location and because of their business skills. The rest of them have fairly marginal operations but the revenues that are generated provide services for their Indian communities and very few Indians get these per capita checks that some people think we all get and that we're all rich and that's just not the case. And again, it's a continual process of educating people about that cause some of them pick up the wrong information, get the wrong impression about things so it's a continuing education campaign that many of us are involved in."

How tribal governments are impacted by the federal budget emphasis on national security

John Echohawk:

"So much of the budget is starting to be deferred over to these national security issues and what that's meant is that the difficulties we usually have trying to get appropriations for Indian programs are made even more difficult by this competing priority of funds for national security. It's made things even tougher and we're seeing that in this appropriation cycle now. We're barely able to have appropriated the same funds that we have appropriated last year before this national security crisis hit and it's very, very difficult, very tough going to ask for increases in all these programs that are woefully inadequate to start with."

The most beneficial piece of federal legislation for tribes in the past 30 years

John Echohawk:

"I think it has to be the Indian Self Determination Act of 1975 because that really implemented this Indian self-determination policy that we had all been pushing for and got Congress officially onboard that concept and what it means. It was really a change in Indian policy because under the old termination policy that of course self determination replaced the thinking of the federal government and the policy makers was that Indian affairs were to be managed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the federal government on our lands until such time as we were able to manage for ourselves. And when that happened then we would be terminated and the federal government through the Bureau of Indian Affairs would leave the reservations and our tribal governments would be eliminated and we would come under the authority of the states. That was their prescription for us. But with the Self Determination Era what happened was we would accept the Bureau of Indian Affairs leaving the reservations or taking a back seat on the reservations but what would come forward was the tribal governments and that's been the biggest development here over the last 30 years has been the growth of modern tribal governments where our tribal institutions have stepped up and began governing our reservations in place of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. And the Self Determination Act facilitated that by providing the funds that usually went to the Bureau of Indian Affairs to govern our reservations and to get those funds over to the tribal governments so the tribal governments could govern our reservations."

Planning for the struggles ahead in light of recent Supreme Court decisions

John Echohawk:

"Well, the Tribal Sovereignty Protection Initiative is an effort by tribal leaders across the country to address what I think is the biggest threat to Indian Country today and that is the big change that we have seen in the decisions of the United States Supreme Court as they affect Native American rights. Throughout this whole 30 year period we've been talking about tribal progress has been driven by and large by favorable decisions of the United States Supreme Court upholding tribal rights in this country. In the last 10 years or so that has changed dramatically as the makeup of the Supreme Court has changed and it's become more conservative. Now the tribes lose virtually every case that goes to the Supreme Court. It used to be that they would take cases that we lost in the lower courts and decide them in our favor or take the cases that we won and affirm them in Supreme Court opinions. But anymore what they do is take cases that the tribes have won in the lower courts and then reverse them and come out with new interpretations, limiting interpretations of tribal rights. And this trend is of great concern to tribal leaders particularly because of two cases that came out last year that established that tribes have virtually no sovereign inherent authority over non-Indians in Indian Country whether it's on fee land owned by non-Indians within Indian Country or whether it's on tribal lands now. The tribes have virtually no authority over non-Indians in our territories and of course this is going to have a devastating impact on our ability to control public health and safety on our lands. It's going to impact our economic development and all of this comes at a time when of course we thought that we had clearly established what our authority was to control things on the reservations and now we find through these recent Supreme Court decisions that we do not have this governmental authority over non-Indians in Indian Country that we thought that we had. And tribal leadership has determined that it's not a good future for our tribes without this authority over non-Indians and it's so grim that we need to do something that's going to be very difficult and that is we need to go to the Congress and share with the Congress our concerns about these Supreme Court decisions and have the Congress reaffirm tribal authority over non-Indians in Indian Country so that we can protect the health and safety of everybody on the reservations and we can also continue to develop our tribal economies in a way that benefits our people and non-Indian people as well. This is going to be a very difficult issue cause it raises of course the basic question of the status of tribes in this country and their authority in this country but it's something that we have to do because the Supreme Court has basically decimated the tribes in terms of their authority over non-Indians on the reservations. We understand that the concern of the Supreme Court primarily has been how the tribal governments treat non-Indians as they exercise authority over them particularly in our tribal courts and the laws relating to the tribes basically empower those tribal courts in past years to decide these issues relating to non-Indians but the court has withdrawn that authority now because of their concern that these tribal court decisions are not subject to review by the Supreme Court, by the federal courts and the court has said as much. They want an opportunity to review all of these decisions of the tribal courts and that's the only way they can insure that non-Indians get treated fairly in our tribal courts. So part of what the tribal leaders are ready to do is to talk to Congress about having their authority over non-Indians restored and in return the tribes are willing to subject their tribal courts to federal court review of their treatment of non-Indians. It's just a very difficult issue that tribes face. Some of them are ready to do that, some of them are not ready to do that just yet."

The need to address not only civil jurisdiction but also criminal misdemeanor jurisdiction

John Echohawk:

"The crime statistics in Indian Country are abominable. While the crime rates across the country generally have gone down, in Indian Country they've gone up and that's primarily because the tribal governments don't have any authority over non-Indians in the criminal context and any prosecutions have to be done by federal or state authorities. And of course they're not really there in our Indian communities so much of the crime that happens does not get prosecuted and the tribes are powerless to do anything about it. So the tribes, many of them want this misdemeanor jurisdiction authority over crimes on reservations so that they can address the crime problem themselves so all these issues are going to Congress because we are not going to win these issues in the Supreme Court. They have basically denied our authority to do that so we have to get Congress to recognize our authority to do that."

Extreme cases have stirred minority descent

John Echohawk:

"In one of these cases last year when the court basically extended their interpretation of the limited authority of tribes over non-Indians on non-Indian land those same limitations over to now jurisdiction over non-Indians on our own Indian lands. They said there's virtually no difference between tribal authority over non-Indians whether they're on non-Indian land in Indian Country or whether they're on Indian land in Indian Country, it doesn't matter who owns the land, the fact of the matter is they're non-Indians and tribes have very limited if no authority over non-Indians anywhere in Indian Country. And this surprised three of the justices so much that six of the justices would all of a sudden announce this interpretation of Indian law that we had virtually no authority over non-Indians even on our own Indian lands that three of the justices in a very vigorous descent said the court has gone way too far in basically ignoring all of their past decisions relating to the authority of tribal governments over non-Indians back to the earliest days of the nation and all of a sudden announced this new doctrine, this new rule of law that takes away from the tribes authority that they have always had that we have to object. We have to descent vigorously and tell the majority of the court that they have made a really wrong decision, a bad decision and a decision judges should not be making because it's not the law of this country, that's not the law of tribal sovereignty. The opinion was written by Justice O'Connor supported by Justice Breyer and Justice Stevens."

The project ahead with Congress

John Echohawk:

"It's going to be a long process, there's going to be a lot of debate involved on all sides about the status of tribal governments and what kind of authority they should have over non-Indians and the impact on the states and local governments and non-Indian people. But it's one that has to be done because otherwise tribes face an uncertain future lacking control over a lot of things that happen in Indian Country that they need to be involved in."

The role of familial support

John Echohawk:

"Well, I've got a wonderful wife and family. They've been very supportive of me in my work even though it takes me away from home quite a bit traveling throughout the country on these cases and various issues. They understand it's important work and that my workplace is basically the whole country and I need to be at my workplace and it's not always in my office at home, it's different places around the country. So they've really been very supportive of me in that regard. I couldn't do it without them."

The values that underpin John Echohawk's work

John Echohawk:

"Well, I believe in the fairness and justice in this country and under the American system and even though our people don't always receive that sometimes we do. And it's really great when we're able to win something and make some progress for our people. And when that fairness and justice doesn't come through then it's very disappointing but at the same time we never give up and we figure another way to try to get the point across and get this fairness and justice that we're due under this system."

Education about the history of Indian nations for both tribal youth and non-Indians

John Echohawk:

"Well, I try to take advantage of every speaking opportunity I get in front of college classes and Indian youth in particular. But on a broader scale we're trying to impact the education systems on or near reservations so that tribal governments get involved more in that. And through the involvement of the tribal governments then they can modify the curriculums and what happens in the schools so that the existence of modern day Native Americans can be taught and appreciated in these schools and so that people come to learn about the history of our Indian nations and our legal status today as Indian nations. And again not only our Native youth but also the non-Indians involved in those same systems that our neighbors come to understand that too."

The greatest contribution of Native Americans to the country

John Echohawk:

"I think it's remarkable that our Native people have been able to maintain their sense of spirituality throughout all of this time that we've had dealings with non-Indians in this country and despite all the terrible things that have happened to us. Our people are still I think very open and caring and that's why they try to preserve their way of life and also continue to try to reach out and share with non-Indian people and try to deal with non-Indian people fairly too in recognizing the place of the human being in the larger universe and in this environment and our obligation to recognize that environment and our place in it and our obligation to take care of it."

The thread in Echohawk's own story he would extend to youth

John Echohawk:

"Well, I think the same thing that my parents engrained in me and my brothers and sisters that education is important. It really helps to understand the world around you and how it works and that you need to have that information to be able to take care of yourself but also to be able to help in your communities and that you have an obligation to do that. Our youth sooner or later at some point in their lives will come to understand those things and I think the earlier they understand that they need this information, they need this education for themselves and for their families and communities the better off they will be. So many of them resist the idea of education but I think once they see how it helps them personally and how it helps their families and communities the better off they're going to be and I think the easier it will be for them to open up and be receptive to educational opportunities."

The legacy Echohawk and his generation will leave

John Echohawk:

"I think I was raised in an era where I'm part of the first generation of Native American people who became professionals in this country, lawyers and doctors and we're able to use that knowledge then for the benefit of our people in a way that never had been done before. I think the assumption was always if our people got educated then we would be like White people and that has not proven to be the case. All of us have used the knowledge and education that we've gotten to benefit our people in our own terms and to continue our Indian ways and I think that has really surprised the American culture generally and has basically given our people a future where we see that our tribes are going to be able to exist in perpetuity."

The Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times series and accompanying curricula are for the educational programs of tribes, schools and colleges. For usage authorization, to place an order or for further information, call or write Institute for Tribal Government – PA, Portland State University, P.O. Box 751, Portland, Oregon, 97207-0751. Telephone: 503-725-9000. Email: tribalgov@pdx.edu.

[Native music]

The Institute for Tribal Government is directed by a Policy Board of 23 tribal leaders,

Hon. Kathryn Harrison (Grand Ronde) leads the Great Tribal Leaders project and is assisted by former Congresswoman Elizabeth Furse, Director and Kay Reid, Oral Historian

Videotaping and Video Assistance

Chuck Hudson, Jeremy Fivecrows and John Platt of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission

Editing

Green Fire Productions

Photo credit:

John Echohawk

NARF

Anthony Allison

Joseph Consentino

Thorney Lieberman

Gary J. Thibault

Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times is also supported by the non-profit Tribal Leadership Forum, and by grants from:

Spirit Mountain Community Fund

Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs

Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde, Chickasaw Nation

Coeur d'Alene Tribe

Delaware Nation of Oklahoma

Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe

Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Indians

Jayne Fawcett, Ambassador

Mohegan Tribal Council

And other tribal governments

Support has also been received from

Portland State University

Qwest Foundation

Pendleton Woolen Mills

The U.S. Dept. of Education

The Administration for Native Americans

Bonneville Power Administration

And the U.S. Dept. of Defense

This program is not to be reproduced without the express written permission of the Institute for Tribal Government

© 2004 The Institute for Tribal Government