Indigenous Governance Database

capable governing institutions

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "Remaking the Tools of Governance: What Can Native Nations Do?"

Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development Co-Director Stephen Cornell discusses the need for Native nations to reclaim and remake their tools of governance in order to meet the nation-building challenges they face today.

Michael K. Mitchell: Perspectives on Leadership and Nation Building

Mohawk Council of Akwesasne Grand Chief Michael K. Mitchell discusses the Akwesasne Mohawk's effort to regain control over their own affairs, and offers his advice to leaders who are working to regain jurisdiction over their lands and resources as well as rebuild their nations.

NNI Forum: Tribal Sovereign Immunity

Tribal sovereign immunity has far-reaching implications, impacting a wide range of critical governance issues from the protection and exertion of legal jurisdiction to the creation of a business environment that can stimulate and sustain economic development. Native Nations Institute (NNI) Radio…

Joseph P. Kalt: Sovereign Immunity: Walking the Walk of a Sovereign Nation

Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development Co-Director Joseph Kalt discusses what sovereign immunity is and what it means to waive it, and share some smart strategies that real governments and nations use to waive sovereign immunity for the purposes of facilitating community and…

Karen Diver: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office

Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Chairwoman Karen Diver shares her Top-10 list of the things she wished she knew before she took office as chairwoman of her nation, stressing the need for leaders to create capable governance systems and build capable staffs so that they focus on…

Two More South Dakota Lakota Tribes Advance Toward Their Own Foster Care Systems, Intending to Replace the State DSS System

The Lakota people have taken another positive step toward preserving their cultural sovereignty and solving the persistent foster care crisis in the state as two more tribes have joined the movement to apply for available federal funding to plan their own tribal-run foster care system... The Lower…

Harvard Project Names 18 Semifinalists for Honoring Nations Awards

The Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development recognizes exemplary tribal government initiatives and facilitates the sharing of best practices through its Honoring Nations awards program. On March 3, the Harvard Project announced its selection of 18 semi-finalists for the 2014…

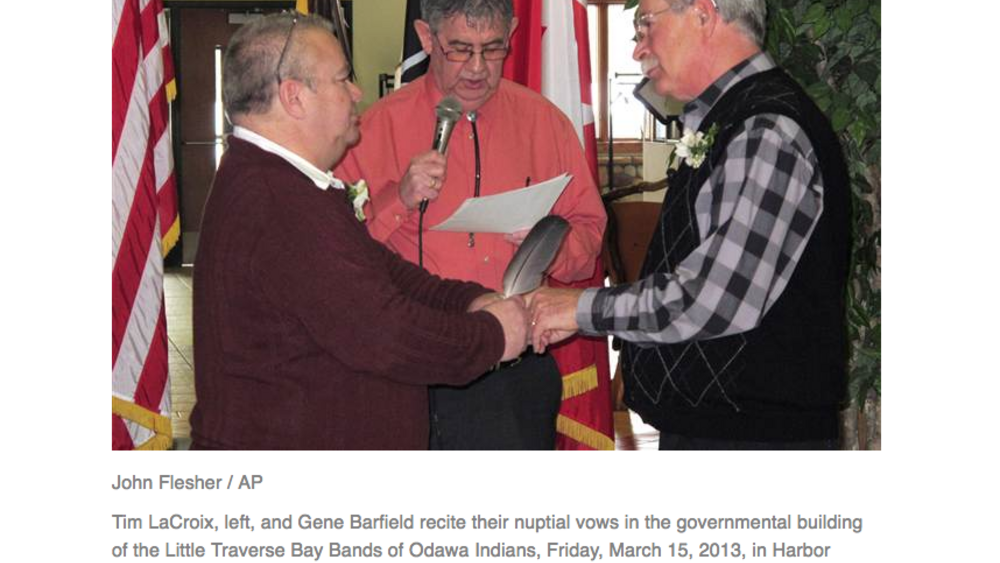

American Indian tribe OKs same-sex marriage, lets gay couple wed

The head of an American Indian tribe in Michigan signed a law approving same-sex marriage on Friday, joining at least two other tribes nationwide in doing so, then immediately wed a gay couple who had been together for 30 years but never thought they would see this day come...

Rebuilding Native Nations: Strategies for Governance and Development

Based on two decades of research, the Native Nations Institute (NNI) at the University of Arizona has worked hard to develop a curriculum for tribal leaders that can assist tribes in achieving true economic self-determination. The essays in Rebuilding Native Nations, published in 2007, are the…

Where Tribal Justice Works

In 2011, a man in northeastern Oregon beat his girlfriend with a gun, using it like a club to strike her in front of their children. Both were members of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. The federal government, which has jurisdiction over major crimes in Indian Country,…

Navigating VAWA's New Tribal Court Jurisdictional Provision

President Obama signed into law the reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), a federal statute that addresses domestic violence and other crimes against women. As initially conceived in 1994, VAWA created new federal crimes and sanctions to fill in gaps, provided training for…

Tribal Land Leasing: Opportunities Presented by the HEARTH Act and Amended 162 Leasing Regulations

This NCAI webinar discussed amendments to the Department of the Interior's 162 leasing regulations as well as practical issues for tribes to consider when seeking to take advantage of the HEARTH Act (Helping Expedite and Advance Responsible Tribal Home Ownership Act of 2012)...

The Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development and its Application to Canadian Aboriginal Business

This lecture is part of a course Stephen Cornell is teaching in Simon Fraser University's Executive MBA in Aboriginal Business and Leadership program. A panel of three joined Dr. Cornell in a discussion about the building of First Nation economies and the role citizen entrepreneurship can play in…

Membertou: Accountable to the Community

Leaders of Membertou First nation explain how a high level of accountability to citizens and partners has been key to its success in both governance and business.

Stephen Cornell: Two Approaches to Building Strong Native Nations

Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development Co-Director Stephen Cornell presents the research findings of the Harvard Project and the Native Nations Institute, specifically the two general approaches that Native nations pursue in an effort to achieve sustainable community and economic…

Joseph P. Kalt: The Nation-Building Renaissance in Indian Country: Keys to Success

Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development Co-Director Joseph P. Kalt presents on the Native nation-building renaissance taking root across in Indian Country, and shares some stories of success.

A Guide to Community Engagement

In this third part of the BCAFN Governance Toolkit: A Guide to Nation Building, we explore the complex and often controversial subject of governance reform in our communities and ways to approach community engagement. The Governance Toolkit is intended as a resource for First Nations leadership. It…

Managing Land, Governing for the Future: Finding the Path Forward for Membertou

This in-depth, interview-based study was commissioned by Membertou Chief and Council and the Membertou Governance Committee, and funded by the Atlantic Aboriginal Economic Development Integrated Research Program to investigate methods by which Membertou First Nation can further increase its…

Navajo Nation Constitutional Feasibility and Government Reform Project

This paper will review three important elements related to the constitutional feasibility and government reform of the Navajo Nation. The first section will outline the foundational principles related to constitutionalism and ask whether constitionalism and the nation-state are appropriate…

Sovereignty Under Arrest? Public Law 280 and Its Discontents

Law enforcement in Indian Country has been characterized as a maze of injustice, one in which offenders too easily escape and victims are too easily lost (Amnesty International, 2007). Tribal, state, and federal governments have recently sought to amend this through the passage of the Tribal Law…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 2

- 3

- 4

- …

- Last page