Indigenous Governance Database

per capita distributions

Per Capita Distributions of American Indian Tribal Revenues: A Preliminary Discussion of Policy Considerations

This paper examines policy considerations relevant to per capita distributions of tribal revenues. It offers Native nation leaders and citizens food for thought as they consider whether or not to issue per capita payments and, if they choose to do so, how to structure the distribution of funds and…

Richard Luarkie: The Pueblo of Laguna: A Constitutional History

In this informative interview with NNI's Ian Record, Laguna Governor Richard Luarkie provides a detailed overview of what prompted the Pueblo of Laguna to first develop a written constitution in 1908, and what led it to amend the constitution on numerous occasions in the century since. He also…

Karen Diver: Nation Building Through the Cultivation of Capable People and Governing Institutions

In this informative interview with NNI's Ian Record, Chairwoman Karen Diver of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa discusses the critical importance of Native nations' systematic development of its governing institutions and human resource ability to their ability to exercise sovereignty…

NNI Indigenous Leadership Fellow: Jamie Fullmer (Part 2)

Jamie Fullmer, former chairman of the Yavapai-Apache Nation, shares what he wished he knew before he first took office, and offers some advice to up-and-coming leaders on how to prepare to tackle their leadership roles. He also discusses what he sees as some keys to Native nations developing…

Ruben Santiesteban and Joni Theobald: Choosing Our Leaders and Maintain Quality Leadership: The Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians

Ruben Santiesteban and Joni Theobald of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians provide an overview of how Lac du Flambeau developed a new approach to cultivating and then selecting quality leaders to lead the Band to a brighter future.

Honoring Nations: Tom Hampson: ONABEN: A Native American Business Network

Former Executive Director of ONABEN Tom Hampson presents an overview of the organization's work to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

John "Rocky" Barrett: A Sovereignty "Audit": A History of Citizen Potawatomi Nation Governance

Citizen Potawatomi Nation Chairman John "Rocky" Barrett shares the history of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and discusses its 40-year effort to strengthen its governance system in order to achieve its goals.

Honoring Nations: Rick Hill: Sovereignty Today

Former Oneida Nation Business Committee Chairman Rick Hill offers his perspectives on sovereignty today through the lens of the challenges facing his nation and the strategies theyr employing to achieve their nation-building goals.

Patricia Ninham-Hoeft: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office (2009)

Oneida Nation Business Committee Secretary Patricia Ninham-Hoeft reflects on her role as a leader for the Oneida Nation and offers advice for newly elected leaders.

Deron Marquez: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office

Former San Manuel Band of Mission Indians Chairman Deron Marquez reflects on his experience as the chief executive of his nation, from his unexpected return to the reservation to building a sustainable economy essentially from scratch.

Tribal Per Capitas and Self-Termination

For many Indian families, tribal per capita payments help meet their most basic needs. They buy food, pay heating bills, make car payments, and open savings accounts. As a Dry Creek Rancheria Band of Pomo Indians leader explains, per capita monies have given historically impoverished Indian…

Economy, distrust complicate allocation of tribal settlement money

When the Obama administration announced in April that it would pay 41 tribes some $1 billion to settle a lawsuit over federal mismanagement of trust funds, many saw it as a sort of stimulus package for Indian Country -- a chance to invest in long-term development and infrastructure, such as schools…

Tribal Per Capita Poverty - How About Disenrollment Bankruptcy?

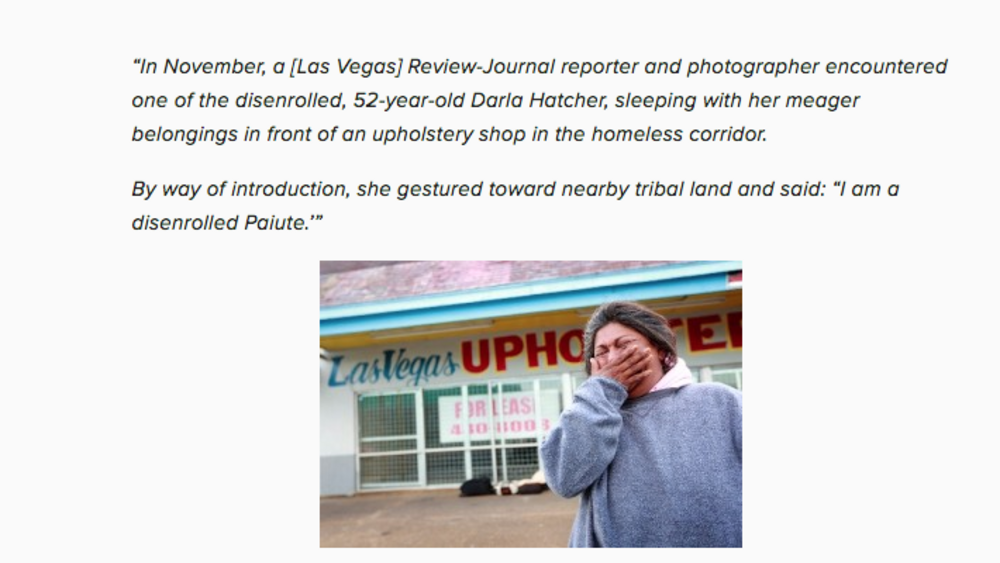

“In November, a [Las Vegas] Review-Journal reporter and photographer encountered one of the disenrolled, 52-year-old Darla Hatcher, sleeping with her meager belongings in front of an upholstery shop in the homeless corridor. By way of introduction, she gestured toward nearby tribal land and said…