Indigenous Governance Database

cultural education

Determi-Nation podcast with Darrah Blackwater

Determi-Nation is a series of conversations with Indigenous people doing incredible things to strengthen sovereignty and self-determination in their communities.

Stephen Roe Lewis: Effective Tribal Leadership for Change

Stephen Roe Lewis has been serving two terms as the Governor of the Gila River Indian Community. He follows a strong tradition and family legacy of leadership for the Akimel O’otham and Pee-Posh people in this desert riparian region of Arizona. Governor Lewis has worked on numerous political…

Governor Stephen Roe Lewis Distinguished Tribal Leader Lecture

Governor Stephen Roe Lewis of the Gila River Indian Community visited the University of Arizona to speak at January in Tucson: Distinguished Tribal Leader Lecture sponsored by the Native Nations Institute and held at the Indigenous Peoples Law & Policy program at James E. Rogers College of Law…

Vernon Masayesva: Self-Governance and Protecting Water

Former Tribal Chairman of the Hopi Nation and Executive Director of Black Mesa Trust, Vernon Masayesva relays his thoughts about advocating for self-governance and protection of water rights for Indigenous people. His pursuits in holding accountability of mining in Hopi territory has made Vernon…

Daryle Rigney: Asserting Cultural Match and Native Nation Building in Australia

Daryle Rigney brings his expertise and first-hand experiences as a citizen of Ngarrindjeri Nation in South Australian to share his thoughts about Native Nation Building for the Ngarrindjeri Nation. He is a Professor of Indigenous Strategy and Engagement at College of Humanities Arts and…

Vernon Masayesva Keynote: Water Ethics Symposium

Vernon Masayesva (Hopi) is the Executive Director of Black Mesa Trust and leading advocate for protecting water resources for the Hopi Nation. He's a Hopi Leader of the Coyote Clan and former Chairman of the Hopi Tribal Council from the village of Hotevilla who has worked for decades…

Greg Cajete: Indigenous governance and sustainability

Greg Cajete, Tewa of the Santa Clara Pueblo and a renowned scholar and author on indigenous education serves as the Director of Native American Studies at the University of New Mexico. His works have merged native history, cultural practices, and knowledge into the cross section of education…

Regis Pecos: Resilience of Culture and Indigenous Heritage

Former Governor, Cochiti Pueblo Regis Pecos speaks to the Native Nation Rebuilders Cohort 2015. He highlights the strength of indigenous heritage and resilience of culture for Native nations to govern themselves.

Leroy Shingoitewa: Self-Governance with Hopi Values

Leroy Shingoitewa, member of the bear clan, and served as chairman of the Hopi tribe and since January 2016, has served as a councilman representing the village of Upper Moenkopi. He recalls the intricacies of governing while maintiang Hopi values and traditions.

Noelani Goodyear Ka'opua: The ongoing journey of Hawai'i sovereignty

Dr. Noelani Goodyear Ka'opua from the Indigenous Politics Faculty within the department of political science at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa speaks about the particulars of handling the issue of soverignty in Hawai’i.

Chairman Dave Archambault II: Laying the Foundation for Tribal Leadership and Self-governance

Chairman Archambault’s wealth and breadth of knowledge and experience in the tribal labor and workforce development arena is unparalleled. He currently serves as the chief executive officer of one of the largest tribes in the Dakotas, leading 500 tribal government employees and overseeing an array…

Leadership Development in the Native Arts and Culture Sector

Burgeoning cultural renewal in Native America and growing mainstream recognition of Native artists and their ideas have resulted in substantial growth in the Native arts and culture sector. The leaders of Native arts and cultural organizations have been a significant force behind this change. They…

Good Native Governance Plenary 3: Innovative Research in Education: Educating Tomorrow's Tribal Leaders

UCLA School of Law "Good Native Governance" conference presenters, panelists and participants Tiffany S. Lee, Sheilah E. Nicholas, and Tarajean Yazzie-Mintz focus on the process of educating tribal leaders, youth, and entire communities through relationships and collaborations. This video…

LeRoy Staples Fairbanks III and Adam Geisler: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office (Q&A)

Leroy Staples Fairbanks III and Adam Geisler field questions from the audience about the role of education in nation building. The discussion focuses on the importance of Native people being grounded in their culture and language, and where and how that education can and should take place.

Native Language: Pathway to Traditions, Self-Identity

Stacey Burns says a transformation has taken place within the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony from something as old as the Washoe, Paiute and Shoshone tribes themselves: their native languages...

Food Sovereignty: How Osage People Will Grow Fresh Foods Locally

Growing fresh and local foods for Osage people is now a revived approach to food sovereignty for the Osage Nation so efforts to find the most successful methods are being looked into by leadership and community members. On Feb. 7, the Oklahoma Department of Agriculture along with the Oklahoma State…

Radical New Way to 'Museum': A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center

Many people think of museums as dusty, static, boring places. They’re where you go if you want to see old bones, old artifacts, and the odd diorama. They’re not living, breathing spaces where cultures come alive. Enter the A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center in Zuni, New Mexico, which has…

Teaching the Whole Child: Language Immersion and Student Achievement

As Congress considers two bills to support Native American language immersion, including the Native Language Immersion Student Achievement Act, it is time to take stock. What does research say about the impact of Native-language immersion on Native students’ academic achievement? We now have 30…

Glimmers of hope on Pine Ridge Indian Reservation

The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation has become emblematic of rural poverty, neglect and the plight of struggling American Indians. But across the reservation, there are glimmers of hope and resistance against the monumental challenges the Lakota people face. In the case of Alice Phelps and the…

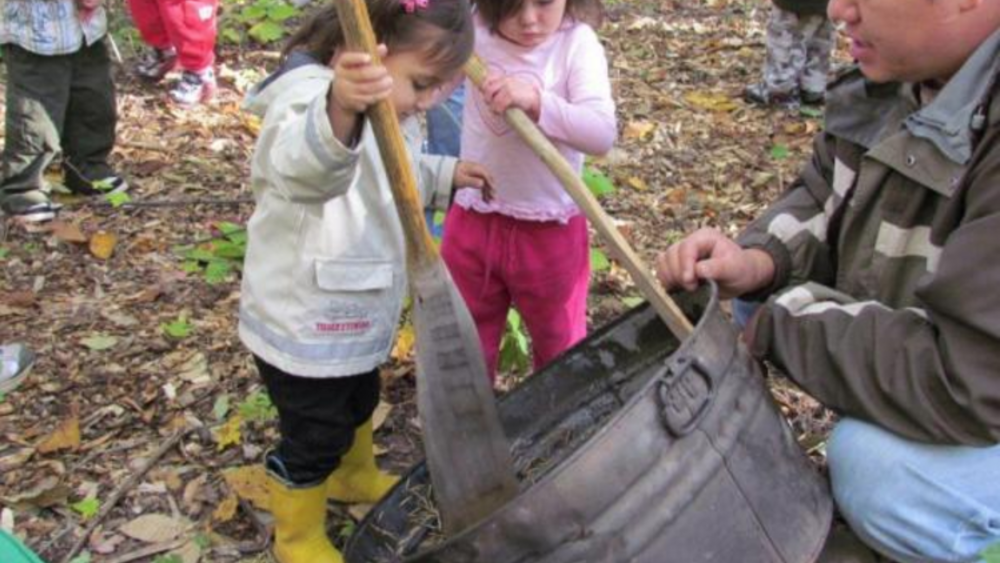

Preserving Culture: 6 Early Childhood Language Immersion Programs

Language immersion schools have proved to be enormously beneficial for young learners’ academics. To quote Dr. Janine Pease-Pretty on Top, Crow, founding president of Little Big Horn College, “Solid data from the Navajo, Blackfeet and Assiniboine immersion schools experience indicates that the…