Indigenous Governance Database

effective management

Indigenous Metadata Bundle Communiqué

Indigenous metadata provides critical organization and structure for Indigenous Peoples’ data to be findable, accessible, interoperable and with proper attribution, which enables governance, decision-making and cultural authority by Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous metadata guides the inclusion of…

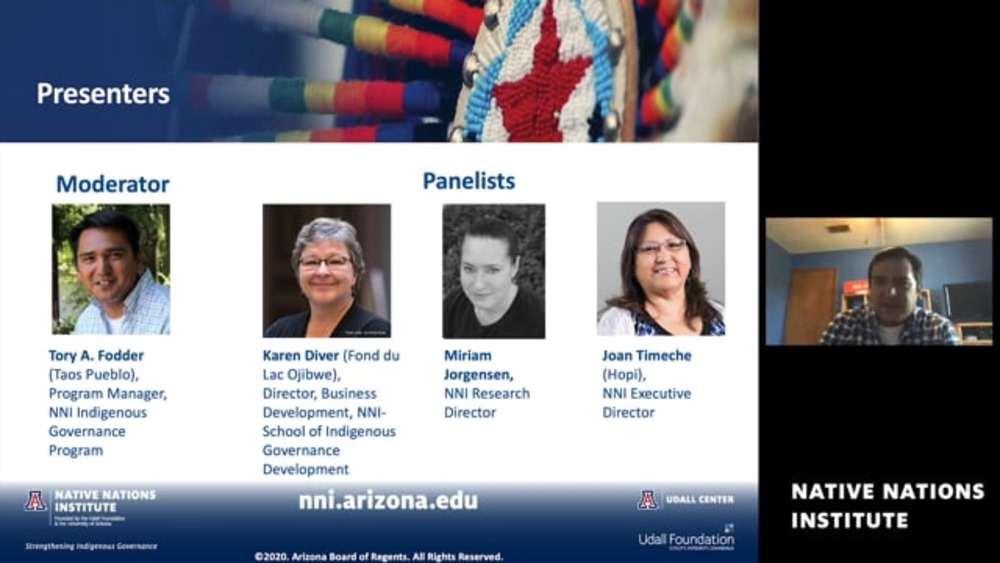

Webinar: Rebuilding Native Nations and Strategies for Governance and Development

The Indigenous Governance Program (IGP) at the University of Arizona has long been at the vanguard of delivering Indigenous Governance Education. To do our part at this critical time, IGP was pleased to offer our January in Tucson Courses in May event free of charge, live streamed via Zoom to…

Rosebud Sioux Tribal Education Department and Code

Responding to disproportionately low academic attendance, achievement, and attainment levels, the Tribe created an education department (TED) in 1990 and developed a Code that regulates and coordinates various aspects of the tribal schools, public schools, and federally-funded Indian education…

Lummi: Safe, Clean Waters

Governed by a five-member, independently elected board that includes two seats that are open to non-tribal fee land owners, the Lummi Tribal Sewer and Water District provides water, sanitary and sewer infrastructure, and service to 5,000 Indian and non-Indian residents living within the external…

Grand Traverse Band's Land Claims Distribution Trust Fund

After 26 years of negotiation with the US government over how monies from a land claims settlement would be distributed, the Band assumed financial control over the settlement by creating a Trust Fund system that provides annual payments in perpetuity to Band elders for supplementing their social…

Honoring Nations: Miriam Jorgensen: Using Your Human and Financial Resources Wisely

NNI Research Director Miriam Jorgensen kicks off the 2004 Honoring Nations symposium with a discussion focused on "Using Your Human and Financial Resources Wisely," In her presentation, she frames key issues and highlights the ways that successful tribal government programs have attracted…

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "Strategic Clarity"

NNI Executive Director Joan Timeche stresses the importance of Native nations having strategic clarity in the development and operation of effective bureaucracies.