Indigenous Governance Database

good governance

The More Indigenous Nations Self Govern, The More They Succeed

Harvard Kennedy School Professor Joseph Kalt and senior director Director Megan Minoka Hill say the evidence is in: When Native nations make their own decisions about what development approaches to take, studies show they consistently out-perform external decision makers like the U.S. Department of…

Indigenous Governance Speaker Series: How to Build a Nation with Susan Masten (Yurok)

Susan Masten (Yurok), former Chairwoman and valuable leader of the Yurok Tribe, joins the Native Nations Institute's Executive Director, Joan Timeche (Hopi), for an engaging discussion on Native nation building, specifically, how she actually helped build the nation. She was critical to the…

Karen Diver: Native leadership and Indigenous governance

Karen Diver is a former Chairwoman of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and former Vice President of the Minnesota Chippewa tribe, while also served as an adviser to President Obama as his Special Assistant for Native American affairs. Her incredible career as renowned Native…

Good Native Governance: Lunchtime Keynote Address

UCLA School of Law "Good Native Governance" conference lunchtime keynote speaker, Joseph P. Kalt discusses research in the areas of good Native governance. This video resource is featured on the Indigenous Governance Database with the permission of the UCLA American Indian Studies…

Good Native Governance Plenary 1: Innovations in Law

UCLA School of Law "Good Native Governance" conference presenters, panelists and participants Carole E. Goldberg, Matthew L.M. Fletcher, and Kristen A. Carpenter discuss law and the issues that Native nations deal with. Goldberg explains the recommendations of the Indian Law and Order Commission…

Good Native Governance: Keynote Address

UCLA School of Law "Good Native Governance" conference keynote speaker, Kevin Washburn, Assistant Secretary — Indian Affairs for the U.S. Department of the Interior, examines how Native nations are engaging so well in self-determination through good governance. This video resource is…

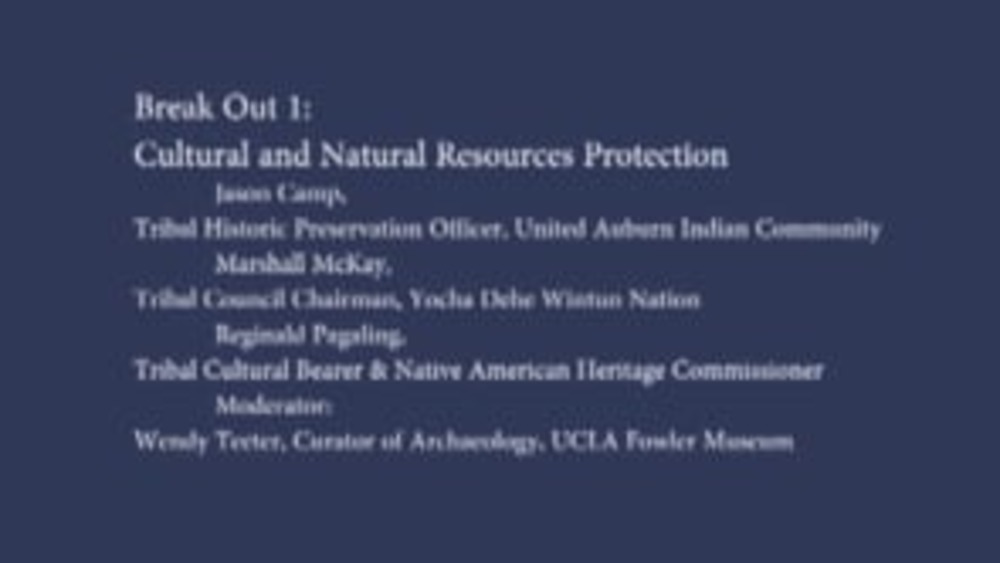

Good Native Governance Breakout 1: Cultural and Natural Resources Protection

UCLA School of Law "Good Native Governance" conference presenters, panelists and participants Reginald Pagaling, Marcos Guerrero, and Marshall McKay discuss their experience with cultural preservation and cooperation with the local and state governements. Reginald addresses the areas of concerns…

From the Good Native Governance: Innovative Research in Law, Education, and Economic Development Conference

Assistant Secretary Kevin Washburn provided a snapshot of Native nations engaging in self-governance reinforcing the notion that "almost anything the federal government can do, tribes can do better" through good governance.

Honoring Nations: The Politics of Change - Internal Barriers, Opportunities and Lessons for Improving Government Performance

Moderator JoAnn Chase facilitates a wide-ranging discussion by a panel of Native nation leaders and key decision-makers about internal barriers inhibiting good governance and opportunities and lessons for improving government performance in Native nations.

Honoring Nations: Robert Yazzie: The Navajo Nation Judicial Branch

Chief Justice Emeritus Robert Yazzie of the Navajo Nation Supreme Court talks about the Navajo Nation Judicial Branch's application of Navajo common law in its jurisprudence as an example of the importance of Indigenous cultural values and common law into the governance systems of Native nations.

Honoring Nations: Stephen Cornell: Achieving Good Governance: Lessons from the Harvard Project & Honoring Nations

Co-director of the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development Stephen Cornell offers a review of how the Honoring Nations program evolved out of the nation-building movement and successes among Native nations.

Honoring Nations: Miriam Jorgensen: Achieving Good Governance: Cross-Cutting Themes

Miriam Jorgensen, Director of Research for the Native Nations Institute and the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development, shares the cross-cutting themes of good governance that exist among the Honoring Nations award-winning programs.

Terrance Paul: Building Sustainable Economies: Membertou First Nation

Chief Terrance Paul shares the keys to a sustainable economy through examples from the Membertou First Nation.

Island First Nation grasps potential of alternative power

While oil pipeline debates, anti-fracking protests and increasing fossil fuel demands embroil the country from coast to coast, a small Vancouver Island First Nation is leading the way on a different path. In the past five years, the seaside T’Sou-ke nation has become a world-renowned leader in…

Indigenous Peoples’ Good Governance, Human Rights and Self-Determination in the Second Decade of the New Millennium – A Māori Perspective

This brief paper addresses the nexus between good governance, human rights and Indigenous peoples’ self-determination particularly from Articles 3-6 and 46 of the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The paper is placed within a Māori good governance context with some…

Does more equitable governance lead to more equitable health care? A case study based on the implementation of health reform in Aboriginal health Australia

There is growing evidence that providing increased voice to vulnerable or disenfranchised populations is important to improving health equity. In this paper we will examine the engagement of Aboriginal community members and community controlled organisations in local governance reforms associated…

Traditional Governance and Adapted Forms of Government

In the early 19th century, British and Canadian governments began interfering directly with the autonomy and sovereignty of Indigenous nations. They forcefully disposed of traditional governments and replaced them with a system of indirect rule effected through newly created offices of Chief and…

Improving Indigenous community governance through strengthening Indigenous and government organisational capacity

Strengthening the organisational capacity of both Indigenous and government organisations is critical to raising the health, wellbeing and prosperity of Indigenous Australian communities. Improving the governance processes of Indigenous organisations is likely to require strengthening of…