Indigenous Governance Database

nation building

Native Nation Building TV: "Bonus Segment on Native Nation Building"

Joan Timeche, Stephen Cornell and Ian Record with the Native Nations Institute at The University of Arizona discuss the "Native Nation Building" television and radio series and the research findings at heart of the series in a televised interview in January 2007.This video resource is featured on…

Honoring Nations: Joseph P. Kalt: Rebuilding Healthy Nations

Harvard Project Co-Director Joseph P. Kalt provides a general overview of the Honoring Nations program and illustrates how people all over the world are learning from the nation-building examples set and the lessons offered by Native nations in the United States.

Honoring Nations: Brian Cladoosby: Sovereignty Today

Swinomish Chairman Brian Cladoosby offers his perspective on what tribal sovereignty means today. He argues that the long-term sustainability of Native nations hinges on their right and ability to decide their own affairs and determine their own futures, and stresses the importance of educating…

Harvard Project Names 18 Semifinalists for Honoring Nations Awards

The Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development recognizes exemplary tribal government initiatives and facilitates the sharing of best practices through its Honoring Nations awards program. On March 3, the Harvard Project announced its selection of 18 semi-finalists for the 2014…

Key to Indian Development: Self-Government

Beginning late in the last century, the economies of Indian nations in the United States began recording a remarkable turnaround. Since the early 1990s, per capita income on Native American reservations has grown three times faster than have incomes in the nation as a whole. American Indians are…

A Better Education for Native Students: The Morongo Method

The Morongo School offers a promising way for Indian nations and communities to educate their children so they have a firm foundation in their own culture, and acquire skills to gain entry and complete college...

Indian Education Must Support Dual Citizenship, Nation-building

In contemporary nation states education is a key institution for the socialization and creation of citizens. Schools are designed to provide common rules of civic understanding and responsibilities. Students are taught to understand the history, goals, and functioning of government. In many ways,…

Successful Tribes Are Reshaping Governance

American Indian communities are often offered up as the gold standard of dysfunction in America. With our high rates of entrenched poverty, we top the lists of addiction, suicide and other social ills. It’s platitude that, frankly, gets tiring to hear. We in the media like to describe the best and…

Tribal Sovereignty Special

What does tribal sovereignty mean in Alaska? KNBA's Joaqlin Estus talks with two experts about the legal basis for tribal sovereignty, and tribal judicial systems at work in Alaska. Hear about a court ruling that Alaska tribes can put land into trust status, tax-free and safe from seizure...

Build Our Nation Convention

A local television news program chronicles the effort of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe to deliberate potential changes to its constitution and system of governance.

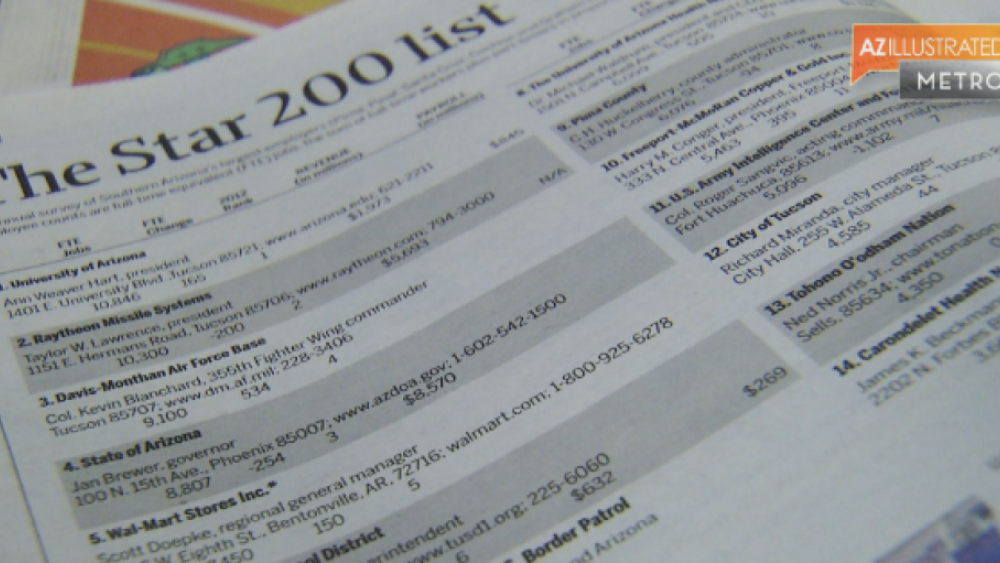

Tohoho O'odham Nation Used as Model For Tribal Governance

The Tohono O'odham Nation, which is in Southern Arizona and northern Mexico, has a tribal governance structure that other Native nations can learn from, and that's why the Native Nations Institute at the University of Arizona is featuring the tribe in some of its courses about governance. The…

Arizona Illustrated: The Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series

Course series director Ian Record and course faculty member Robert A. Williams, Jr. appear on Arizona Public Media's "Arizona Illustrated" evening news television program to discuss the Native Nations Institute's groundbreaking "Rebuilding Native Nations: Strategies for Governance and Development"…

Native Nation Rebuilders Speak

Participants in the Bush Foundation's Native Nation Rebuilders Program offer their personal perspectives on nation building and share their experiences in the program.

Stephen Cornell: Two Approaches to Building Strong Native Nations

Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development Co-Director Stephen Cornell presents the research findings of the Harvard Project and the Native Nations Institute, specifically the two general approaches that Native nations pursue in an effort to achieve sustainable community and economic…

Joseph P. Kalt: The Nation-Building Renaissance in Indian Country: Keys to Success

Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development Co-Director Joseph P. Kalt presents on the Native nation-building renaissance taking root across in Indian Country, and shares some stories of success.

Enabling the Data Revolution: An International Open Data Roadmap

Open data in the context of indigenous peoples and communities can be understood as a double-edged sword. On the one hand, open data can help indigenous communities, both internally and externally. Internally, it can be used to inform policy, allocate resources, and set a vision for indigenous…

In Defense of Tribal Sovereign Immunity: A Pragmatic Look at the Doctrine as a Tool for Strengthening Tribal Courts

Although the doctrine of tribal sovereign immunity was recently upheld by the Supreme Court in Michigan v. Bay Mills Indian Community, its existence continues to be attacked as antiquated and leading to unfair results. While most defenses of tribal sovereign immunity focus on how the doctrine is a…

First Nation Constitutions

A constitution is a solid foundation for First Nations to move ahead in self-government and in nation-building activities. Your constitution will be specific to your community. It should address your community's sense of itself, how you are governed, how the membership has input into governance,…

Best Practices Case Study (Inter-Governmental Relations): Sliammon First Nation

In 2002, the City of Powell River, on the Sunshine Coast in south-western B.C., began construction on a seawalk park. The project inadvertently destroyed or disturbed significant cultural sites of Sliammon First Nation including petroglyphs and shell middens. Deeply concerned by the site impact and…

Statement before the United States Senate Committee on Indian Affairs Oversight Hearing on Economic Development

Why is it that, amidst the well-documented and widespread poverty and social distress that characterize American Indian reservations overall, an increasing number of Native nations are breaking old patterns and building economies, social institutions, and political systems that work? What explains…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 2

- 3

- 4

- …