Indigenous Governance Database

nation-owned enterprises

Cecil F. Antone: Nation-Owned Businesses: Gila River Telecommunications, Inc.

Former Gila River Indian Community Lieutenant Governor Cecil F. Antone provides an brief overview of the evolution and growth of Gila River Telecommunications, Inc. (GRTI), an enterprise of the Gila River Indian Community.

Helen Ben: Nation-Owned Businesses: The Meadow Lake Tribal Council

Former Meadow Lake Tribal Council (MLTC) Chief Helen Ben provides an overview of the various enterprises owned by MLTC, an intertribal organization formed for economic development purposes.

Brian Titus: Nation-Owned Enterprises: Osoyoos Indian Band Development Corporation

Osoyoos Indian Band Development Corporation (OIBDC) Chief Operating Officer Brian Titus provides an overview of OIBDC and the reasons for its success, notably the great lengths it goes to educate Osoyoos citizens about the corporation's activities and overall health.

Michael Taylor: Nation-Owned Businesses: Quil Ceda Village

Tulalip Tribal Attorney Michael Taylor discusses Tulalip's rationale for taking the unique step of creating Quil Ceda Village, a federally chartered city, and the benefits this approach has brought the Tulalip Tribes.

Diane Enos: Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community Economic Development

Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community (SRPMIC) President Diane Enos provides an overview of SRPMIC's effortto build a diversified economy, the institutional keys to make that effort a success, and the cultural principles SRPMIC abides by as it engages in economic development.

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "The Politics-Enterprise Balance"

Native leaders and scholars share their thoughts about how Native nations can effectively manage the relationship between their governments and the businesses they own and operate.

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "Rules are More Important than Resources to Enterprise Success"

Professor Joseph Kalt discusses the importance of sound laws, codes, policies and other rules to the building of diversified, sustainable economies in Indian Country and everywhere else around the world.

Jerry Smith: Building and Sustaining Nation-Owned Enterprises (2009)

Laguna Development Corporation President and CEO Jerry Smith shares the lessons he has learned about building and sustaining Native nation-owned enterprises, in particular the critical step of creating a formal separation between tribal politics and the day-to-day management of those enterprises.

Jerry Smith: Building and Sustaining Nation-Owned Enterprises (2008)

Laguna Development Corporation President and CEO Jerry Smith discusses the evolution and growth of the Pueblo of Laguna's diversified economy, and the importance of building an infrastructure of laws and rules in ensuring the success of Laguna's nation-owned enterprises.

Native Nation Building TV: "Building and Sustaining Tribal Enterprises"

Guests Lance Morgan and Kenneth Grant explore corporate governance among Native nations, in particular the added challenge they face in turning a profit as well as governing effectively. It focuses on how tribes establish a regulatory and oversight environment that allows nation-owned enterprises…

Ho-Chunk, Inc. CEO Receives Award from U.S. Department of Commerce Agency

Lance Morgan launched the Ho-Chunk, Inc. in 1994 as the economic development corporation of the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska. Now the president and CEO is receiving the Advocate of the Year Award by the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Minority Business Development Agency (MBDA) at the end of this…

New economic hope on Pine Ridge Reservation

When I read the Lakota Country Times I am heartened by the economic progress that oftentimes is hidden in the more alarming media reports of rampant alcoholism and the resulting horrors that the disease brings to the communities there on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. There is hope to be had…

UW Names Colville Tribal Federal Corp. Minority Business of the Year

The tribal business for the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation in North Central Washington–the Colville Tribal Federal Corp., or CTFC–recently won the 2013 William D. Bradford Minority Business of the Year Award. It’s the granddaddy of seven awards given annually by the University of…

Key to Indian Development: Self-Government

Beginning late in the last century, the economies of Indian nations in the United States began recording a remarkable turnaround. Since the early 1990s, per capita income on Native American reservations has grown three times faster than have incomes in the nation as a whole. American Indians are…

Rosebud Sioux Tribe boosts local economy

The Rosebud Sioux Tribe, located in the second poorest country in South Dakota, is making moves to create a way to not only save money for the tribal membership, but also create jobs. "We live in an economically depressed area, so we have to find every small way we can to help people locally,"…

Oneidas want locally produced food on local tables

The Oneida Tribe of Indians’ foray into establishing a food hub in their community is proving to be so successful that they’d like to see it spread throughout the county. Products that are grown and processed on Oneida land have been feeding the tribe’s elementary students and elderly for some time…

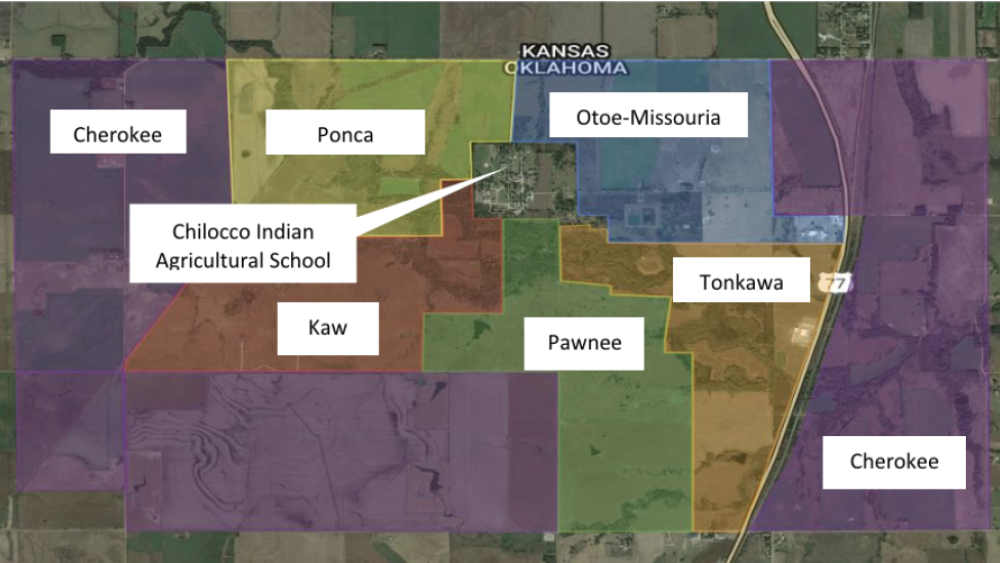

Cherokee Wind Energy Development Feasability and Pre-Construction Studies

Cherokee Nation Businesses (CNB) received a grant from the US Department of Energy to explore feasibility and pursue development of a wind power generation facility on Cherokee land in north-central Oklahoma. This project followed several years of initial study exploring the possibility of…

Tribal Strength Through Economic Diversification

The potential impacts of Internet gaming legalization was a major topic at last month’s National Indian Gaming Association (NIGA) convention. Another critical topic, not surprisingly, was economic diversification and Tribes’ ability to pursue and manage the process of planning for change.…

Oklahoma City University Study Reveals Substantial Economic Impact of the Chickasaw Nation on Oklahoma's Economy

The contribution and impact of the Chickasaw Nation on the economy of Oklahoma exceeds $2.4 billion dollars according to an economic impact analysis released today by the Steven C. Agee Economic Research & Policy Institute at Oklahoma City University. The report, "Estimating the Oklahoma…

Blackfeet: Stocking the Aisles

...Although Glacier Family Foods adds 56 new employees to the Blackfeet Reservation’s year-round workforce, the people behind the store’s creation hope it will do much more than create immediate jobs. For the last 20 years, members of the Blackfeet Tribal Business Council and the community bounced…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …

- Last page