Indigenous Governance Database

strategic visioning

Patricia Riggs: The Role of Citizen Engagement in Nation Building: The Ysleta del Sur Pueblo Story

Patricia Riggs, Director of Economic Development for Ysleta del Sur Pueblo (YDSP), discusses how YDSP has spent the past decade developing and fine-tuning its comprehensive approach to engaging its citizens in order to identify and then achieve its nation-building priorities. This video resource…

Sophie Pierre: Enacting Self-Determination and Self-Governance at Ktunaxa

In this informative interview with NNI's Ian Record, Sophie Pierre, longtime chief of the Ktunaxa Nation, discusses Ktunaxa's ongoing effort to reclaim and redesign their system of governance through British Columbia's treaty process, specifically Ktunaxa's citizen-led process to develop a new…

Paulette Jordan: Engaging the Nation's Citizens and Effecting Change: The Coeur d'Alene Story

Paulette Jordan, citizen and council member of the Coeur d'Alene Tribe in Idaho, discusses the importance of Native nation leaders being grounded in their culture and consulting the keepers of the culture (their elders) so that they approach the leadership challenges they face with the proper…

Paulette Jordan and Arlene Templer: Engaging the Nation's Citizens and Effecting Change (Q&A)

Paulette Jordan and Arlene Templer field questions from the audience, offering more details about how they mobilized their fellow tribal citizens to buy into the community development initiatives they were advancing.

Chris Hall: Cultivating Constitutional Change at Crow Creek

Native Nations Institute's Ian Record conducted an informative interview with Chris Hall, a citizen of the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe and a member of Cohort 4 of the Bush Foundation's Native Nation Rebuilders program. Hall discusses Crow Creek's current effort to reform its constitution and the…

Ned Norris, Jr.: Strengthening Governance at Tohono O'odham

Tohono O'odham Nation Chairman Ned Norris, Jr. discusses how his nation has systematically worked to strengthen its system of governance, from creating an independent, effective judiciary to developing an innovative, culturally appropriate approach to caring for the nation's elders.

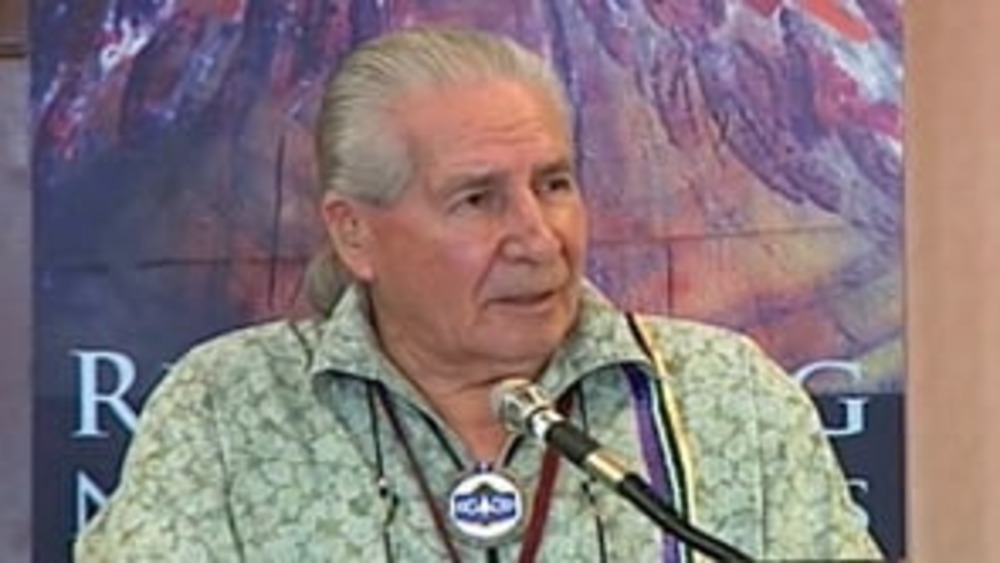

Honoring Nations: Rick George: The Umatilla Basin Salmon Recovery Project: Building on Success

Rick George, former Program Manager for Rights Protection and Environmental Planning with the Confederated tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, shares what he sees as the foundational characteristics of the Umatilla Basin Salmon Recovery Project and other examples of successful,…

Honoring Nations: Manley Begay: So You Have a Great Program...Now What?!

"Forward-thinking" is often used to describe innovative programs. In remarks designed to frame the symposium session "So You Have a Great Program...Now What?!", Manley A. Begay, Jr. talks about strategic orientation, planning, and implementation as critical to sustaining the success of tribal…

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "What Effective Bureaucracies Need"

Native leaders offer their perspectives on the key characteristics that Native nation bureaucracies need to possess in order to be effective.

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "Strategic Clarity"

NNI Executive Director Joan Timeche stresses the importance of Native nations having strategic clarity in the development and operation of effective bureaucracies.

Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times: Kathryn Harrison

Produced by the Institute for Tribal Government at Portland State University in 2004, the landmark “Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times” interview series presents the oral histories of contemporary leaders who have played instrumental roles in Native nations' struggles for sovereignty, self-…

Ben Nuvamsa: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office

Former Chairman of the Hopi Tribe Ben Nuvamsa speaks about his tenure as the elected chief executive of his nation, and how the governance issues he and his nation have experienced in recent years offer important lessons to other Native nations.

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "The Strategic Approach to Leadership"

Native leaders discuss why it is important for Native nation leaders to take a strategic approach to leadership, stressing that the decisions they make must be made with the culture and values of their people and the next seven generations in mind.

Catalina Alvarez: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office

Vice Chairwoman of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe Catalina Alvarez shares what she wishes that she knew before she first took office, and focuses on the importance of elected leaders understanding -- and confining themselves to performing -- their appropriate roles and responsibilities.

Robert McGhee: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office

Treasurer of the Poarch Band of Creek Indians Robert McGhee shares some of the things that he wished he knew before he first took office. He also discusses how he and his elected leader colleagues have built a team approach to making informed decisions on behalf of their constituents.

Herminia Frias: Engaging the Nation's Citizens and Effecting Change

Herminia Frias, former Chairwoman of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe, discusses the citizen engagement challenges she encountered when she took office as an elected leader of her nation, and shares some effective strategies that she used to engage her constituents and mobilize their participation in and…

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "Why are Some Native Nations More Successful than Others?"

Native leaders offer their perspectives on why some Native nations have proven more successful than others in achieving their economic and community development goals.

Peterson Zah and Manley A. Begay, Jr.: Strategic Thinking and Planning: Navajo Nation Permanent Trust Fund (Q&A)

Manley Begay and Peterson Zah field questions from the audience concerning the Navajo Nation Permanent Trust Fund and how they and others worked to mobilize and sustain the citizen support necessary to keep the fund intact and allow it to grow.

Patricia Ninham-Hoeft: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office (2009)

Oneida Nation Business Committee Secretary Patricia Ninham-Hoeft reflects on her role as a leader for the Oneida Nation and offers advice for newly elected leaders.

Patricia Ninham-Hoeft: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office (2008)

Oneida Nation Business Committee Secretary Patricia Ninham-Hoeft reflects on her experience as a leader of her nation, and shares a list of the five leadership skills she wished she had mastered before she took office.