Indigenous Governance Database

Intergovernmental Relations

How to Protect Tribal Lands From Our Deadliest Enemies

In 2001, the U.S. Supreme Court dealt a severe below to Indian sovereignty when it decided Nevada v. Hicks, suggesting to states and counties that when their cops are investigating off-reservation crimes, they need not obtain tribal court warrants to conduct searches or arrests on tribal land. The…

Indian Nations Are Still Fighting the U.S. Cavalry

Throughout the 19th Century the U.S. Cavalry perpetrated the genocide of Indian People. Today’s Cavalry–federal, state and local police–are no longer committed to extermination. But American cops’ flagrant disregard for tribal self-governance when carrying out law enforcement activities on Indian…

Tribes Recondition Steelhead to Bring Back Endangered Trout

The notion of “reconditioning steelhead” might sound outlandish, even a bit ominous, at least when applied to an animal. Reconditioning is what’s done to prepare discarded electronics for resale, and the word carries connotations of recycling. How does one recycle a fish? It turns out, though, to…

Dayton signs tribal consultation executive order

With the White Earth Nation flag and tribal and state representatives standing behind him, Gov. Mark Dayton signed an executive order Thursday directing state agencies to develop policies to guide them when working with tribal nations...

Investing in Fish, Preserving Red Cliff Culture

Small fingerlings roiled the water in the translucent plastic tubs placed before ready volunteers in the Red Cliff tribal fish hatchery at Wisconsin’s northern edge. The agitated three- to six-inch coaster brook trout–known as fry–made the water appear to be boiling. A mild anesthetic was added and…

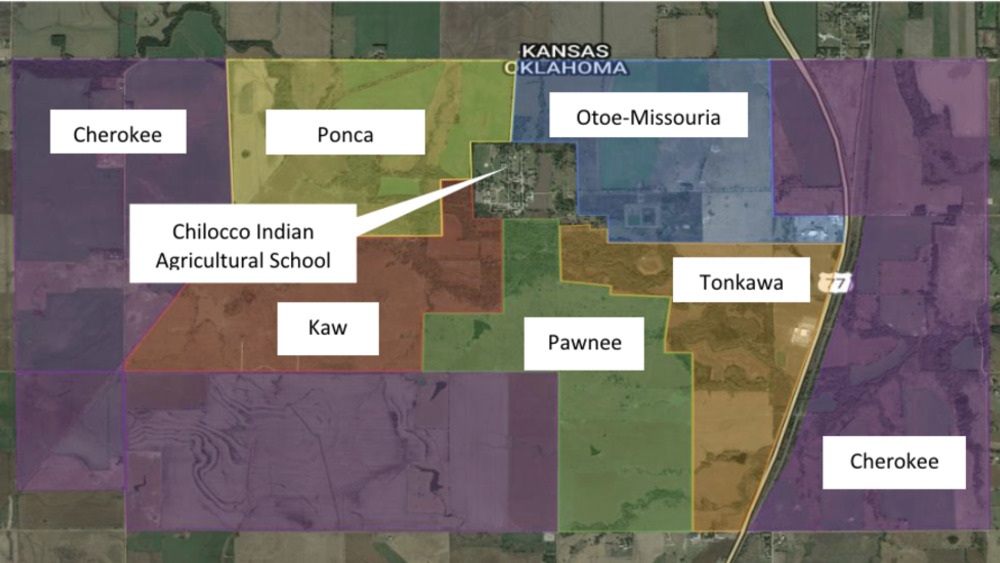

Cherokee Wind Energy Development Feasability and Pre-Construction Studies

Cherokee Nation Businesses (CNB) received a grant from the US Department of Energy to explore feasibility and pursue development of a wind power generation facility on Cherokee land in north-central Oklahoma. This project followed several years of initial study exploring the possibility of…

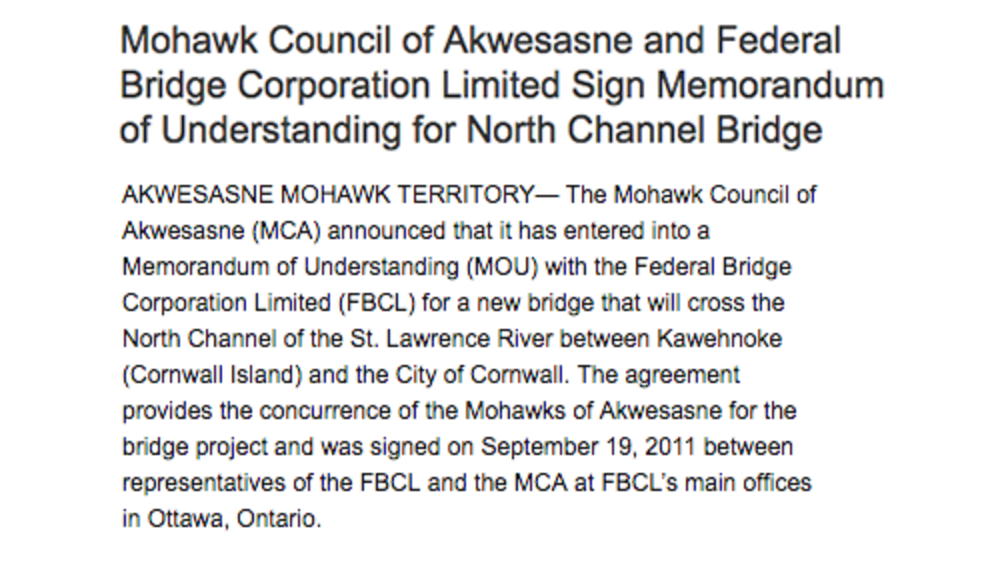

Mohawk Council of Akwesasne and Federal Bridge Corporation Limited Sign Memorandum of Understanding for North Channel Bridge

The Mohawk Council of Akwesasne (MCA) announced that it has entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Federal Bridge Corporation Limited (FBCL) for a new bridge that will cross the North Channel of the St. Lawrence River between Kawehnoke (Cornwall Island) and the City of Cornwall.…

New Leadership for Tubatulabal Tribe; Recognition, Economic Development Among Top Priorities

The new year had barely dawned and Tubatulabal Tribe Chairman Robert Gomez was hard at work on the priorities he and the council had established for the year. It’s a heavy load: Federal recognition. Economic development. Professional development for tribal leadership. Community outreach. Continued…

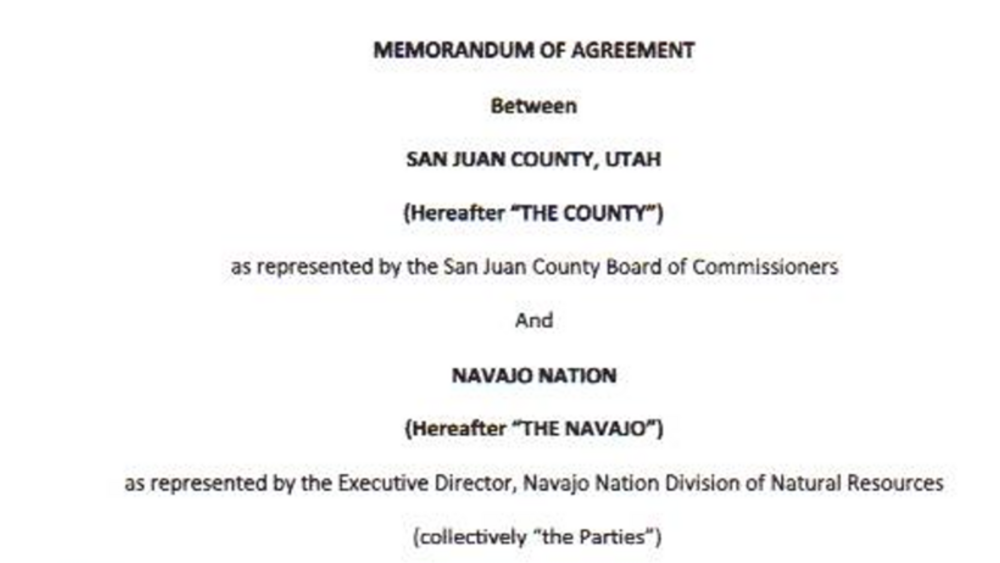

Agreement Signed Between Navajo Nation & San Juan County Utah

Navajo Nation President Ben Shelly signed a groundbreaking agreement San Juan County Commissioners Tuesday morning. President Shelly and the commissioners entered into a memorandum of agreement focused on planning collaboration to develop land use recommendations for state and federal lands within…

Council of Energy Resource Tribes Enters $3 Billion Biofuels and Bioenergy Agreement

The Council of Energy Resource Tribes (CERT), an Inter-Tribal organization comprised of 54 U.S. tribes and four First Nation Treaty Tribes of Canada, has entered into a long-term development agreement for up to $3 billion in biofuels and bioenergy projects, states a CERT press release...

Advancing the State-Tribal Consultation Mandate

This summer, in the face of an impending private land sale of Pe’Sla, a Lakota/Dakota/Nakota Indian sacred site in the Black Hills, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, S. James Anaya, directed that authorities in South Dakota “engage in a process of…

White Earth and Tsleil-Waututh Nations Partner on Community Wind Power

Two tribes, from different sides of the 49th Parallel, are reuniting Turtle Island with a business deal. A First Nations—owned company in British Columbia will supply wind power to the White Earth Community Service Center in Naytahwaush and to the Ojibwa Building Supplies facility in Waubun, the U.…

Tribal Sovereignty Special

What does tribal sovereignty mean in Alaska? KNBA's Joaqlin Estus talks with two experts about the legal basis for tribal sovereignty, and tribal judicial systems at work in Alaska. Hear about a court ruling that Alaska tribes can put land into trust status, tax-free and safe from seizure...

Coming Back: Restoring the Skokomish Watershed

Members of the Skokomish Watershed Action Team have been collaborating for a decade on how to best restore the Skokomish watershed, located at the southern end of Hood Canal, in western Washington. From federal agencies to the Skokomish Tribe to private citizens, this is the story of how these very…

Vice President Biden Speaks at the 2014 White House Tribal Nations Conference

On December 3, 2014, Vice President Joe Biden addressed the 2014 White House Tribal Nations Conference. At the conference, leaders from the 566 federally-recognized Native nations engaged with the President, Cabinet Officials, and the White House Council on Native American Affairs on key issues…

2015 NCAI State of Indian Nations

During the annual State of Indian Nations address, NCAI President Brian Cladoosby, chairman of the Swinomish Nation, called on Congress and the Obama Administration to follow through on a policy action plan to improve economic opportunity, education, and innovation in Indian Country and for the…

Our Journey - Our Choice - Our Future: Maa-nulth Treaty Legacy

On April 1, 2011, the Maa-nulth First Nations completed what has been a long journey to self-determination. It was an historic day for all, and a day of celebration for the Huu-ay-aht, Ka:’yu:’k't’h/Che:k’tles7et’h, Toquaht, Uchucklesaht, and Ucluelet people. New Journey Productions worked with the…

Saving the Ocean: River of Kings, Part 2

An unusual coalition of tribal leaders, private partners and government agencies is working to restore Washington's Nisqually River from its source in the glaciers of Mount Rainier to the estuary that empties into Puget Sound. Led by the Nisqually tribe, the restoration aims to fill the river once…

Bringing Our Children Home: An Introduction to the Indian Child Welfare Act

This six-minute trailer introduces viewers to a documentary film (currently in development) that examines the impact of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA). The documentary is the product of an ongoing collaboration between the Mississippi Courts, Child Welfare Agency, the Mississippi Band of…

Cigarette smuggling and the Akwesasne Mohawk Reserve

In this CBC Television news report from 1988, reporter Bruce Garvey takes a long look at the selling -- some call smuggling -- of tax-free cigarettes at the Akwesasne Indian Reserve. Garvey presents this report on the difficulties created by the unique situation of the Akwesasne Indian Reserve,…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 8

- 9

- 10

- …

- Last page