Indigenous Governance Database

Laws and Codes

Cass Board, Leech Lake Tribal Council highlight cooperative efforts

The cooperation and partnerships between Cass County and the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe in recent years have not only been successful but apparently are highly unusual, both state- and nationwide. Time and again at the April 24 joint meeting of the county board and tribal council, at Northern Lights…

BIA Head Kevin Washburn Speaks to ICTMN About Bay Mills and the Need to Resolve Water Rights

Interior Secretary — Indian Affairs Kevin K. Washburn was in New York City in September as the historic Peoples’ Climate March and the United Nations General Assembly opened its 69th regular session with the first World Conference on Indigenous Peoples, where he added to our excitement here at…

What Is Indigenous Self-Determination and When Does it Apply?

Self-determination is an expression often used in discussion of indigenous goals. However, the meaning of self-determination varies among Indigenous Peoples, scholars, international documents, and nation states. The most common meaning of self-determination suggests that peoples with common…

Tribes reach key milestone with jurisdiction provisions of VAWA

The tribal jurisdiction provisions of the the Violence Against Women Act became effective nationwide on Saturday, clearing the path for non-Indians to be held accountable for abusing their Indian partners. Congress enacted S.47 to recognize tribal authority to arrest, prosecute and punish non-…

As old ways faded on reservations, tribal power shifted

Long before the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act transformed tribal government, before nepotism and retaliation became plagues upon reservation life, there were nacas. Headsmen, the Lakota and Dakota called them. Men designated from their tiospayes, or extended families, to represent their clans…

The Bay Mills Case: An Opportunity for Native Nations

On May 27th, the U.S. Supreme Court finally handed down its decision in the Michigan v. Bay Mills Indian Community case. The good news for Native nations is that the Court upheld the doctrine of tribal sovereign immunity, opting not to carry out any of the doomsday scenarios many suggested could…

Seneca Nation Implements Native Plant Policy

The Seneca Nation of Indians are spearheading a movement to reintroduce more indigenous flora to public landscapes on tribal lands in Upstate New York. The tribal council unanimously approved a policy that mandates all new landscaping in public spaces on Seneca lands exclusively be comprised of…

Tulalips wield new power against domestic violence

The Tulalip Tribes are now one of just three Native American tribes in the country to take advantage of a federal program designed to better combat domestic violence on tribal lands. In an agreement signed with the U.S. Attorney’s Office Friday during a regular meeting of the Tribes’ board of…

Arizona tribe set to prosecute first non-Indian under a new law

Tribal police chief Michael Valenzuela drove through darkened desert streets, turned into a Circle K convenience store and pointed to the spot beyond the reservation line where his officers used to take the non-Indian men who battered Indian women. “We would literally drive them to the end of the…

Dismembering Natives: The Violence Done by Citizenship Fights

Outside Indian Country most don't realize that over the past 10 years, several thousand people have had their tribal citizenship status terminated. Most were not dismembered for wrongdoing or adopted by other Native nations. They were simply identified by their elected officials as allegedly no…

Passamaquoddy Tribe Amends Fishery Law to Protect Its Citizens from State Threat

The Passamaquoddy Tribe’s fishery law has been amended to implement individual catch quotas for the lucrative elver season that began on April 5. While the quota system conforms to a new state law, Passamaquoddy leaders stressed that the change was made to both protect tribal citizens and conserve…

Tribal Rights Legend and Leader Billy Frank Jr. Walks On

In 2004, we celebrated 30 years since the Boldt Decision of 1974, the landmark Indian fishing rights victory, that Billy Frank Jr. fought so hard for.“Frank is widely credited as conscience and soul of the efforts by Indian people in Washington to secure their rights to a fair share of fish on…

Red Lake 15 years later: Historic agreement the Red Lake Band of Chippewa and Minnesota DNR signed in April 1999 produced walleye recovery

As Al Pemberton recalls, it was about three years after the Red Lake Band of Chippewa and the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources signed an agreement to restore walleye populations in Upper and Lower Red lakes that he saw the true potential for the big lakes’ recovery. The agreement, which…

Citizen Stewards: Chickasaw Nation Technicians Monitor Water Quality

Regulations and laws about environmental quality abound, yet the Chickasaw Nation has little use for them. Its citizens do not need legislation to inform them that they are stewards of the land. It is, of course, an immutable fact of existence. And Chickasaw Nation Environmental Services…

Preserving Indigenous Democracy

When Europeans first came to the Americas they took note of the democratic processes they observed in most indigenous nations. Indigenous political relations were usually decentralized, consensus based, and inclusive. Indigenous democracies may not seem remarkable by contemporary standards, but…

Disenrollment Demands Serious Attention by All Sovereign Nations

For most people, their sense of who they are–their identity–is at least partially defined from connection to others and to a community. When individuals are forced to sever those connections, the consequences can be devastating. Unfortunately, all too often in tribal disenrollment conflicts–like…

Living Her Dream: Eldena Bear Don't Walk Discusses Her Law Career

Eldena Bear Don’t Walk is living out her childhood dream. The youngster who imagined one day becoming a lawyer has done exactly that – and more. She has been an appellate judge for eight years, serving almost every tribe in Montana. At the St. Ignatius-based Bear Don’t Walk Law Office, she works as…

Indigenous languages crucial to cultural flourishing

I believe our languages to be so central to who we are as Indigenous peoples, that I cannot discuss our present or our future without reference to languages. The oppression we have faced, and continue to face, does not define us in the way our languages do. Our resilience, and the fact that we have…

Pascua Yaqui gain added power to prosecute some non-Indians

Southern Arizona’s Pascua Yaqui Tribe is one of the first Native nations in the country to earn legal standing to prosecute outsiders who attack women on tribal lands. The Pascua Yaquis – along with the Tulalip Tribes of Washington and the Umatilla Tribes of Oregon – have been been awarded special…

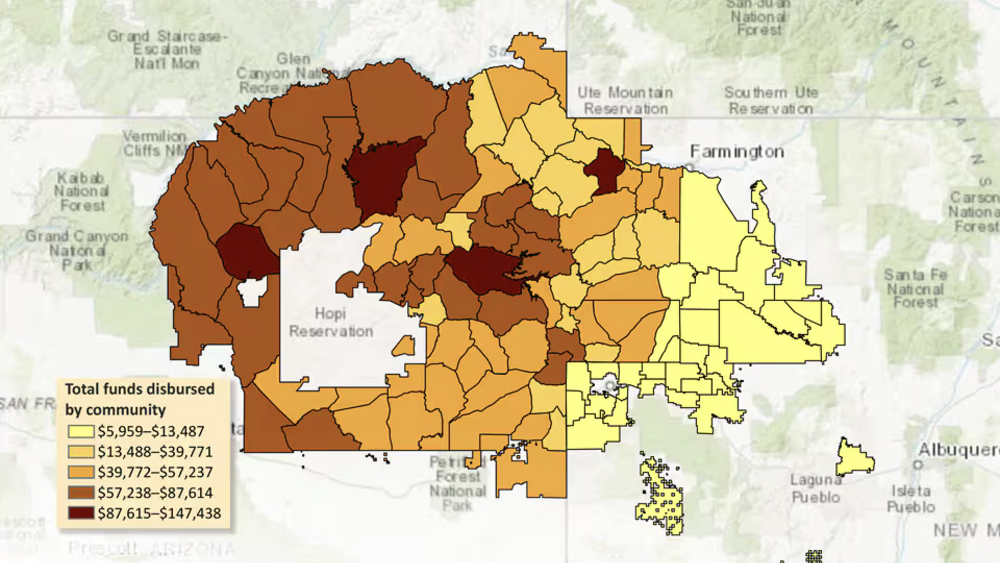

The Navajo Nation Healthy Diné Nation Act: A Two Percent Tax on Foods of Minimal-to-No Nutritious Value, 2015–2019

Our study summarizes tax revenue and disbursements from the Navajo Nation Healthy Diné Nation Act of 2014, which included a 2% tax on foods of minimal-to-no nutritional value (junk food tax), the first in the United States and in any sovereign tribal nation. Since the tax was implemented in 2015,…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 6

- 7

- 8

- …

- Last page