Indigenous Governance Database

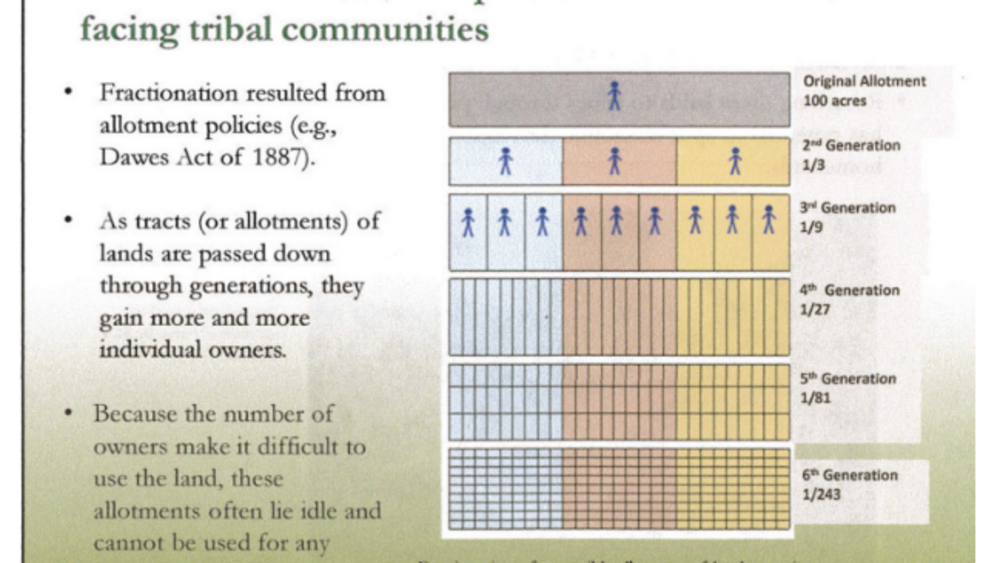

allotment

The Indian Reorganization Act at 80 years

At Pine Ridge, daily controversy surrounds the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. Congress enacted the IRA on June 18, 1934. However, the voting requirement was drastically altered just three days prior. This amendment (H.R. 7781, 49 Stat., 378) dated June 15, 1934, lowered the overall voting…

Indigenous Land Management in the United States: Context, Cases, Lessons

The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) is seeking ways to support First Nations’ economic development. Among its concerns are the status and management of First Nations’ lands. The Indian Act, bureaucratic processes, the capacities of First Nations themselves, and other factors currently limit the…

Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Monitors Program

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is located on 2.3 million acres of land in the central regions of North and South Dakota. Land issues rose to the forefront of tribal concerns after events such as allotment, lands flooding after the Army Corps of Engineers built a series of dams adjacent to the Tribe…

Swinomish Cooperative Land Use Program

Based on a memorandum of agreement between the Tribe and Skagit County, the Swinomish Cooperative Land Use Program provides a framework for conducting permitting activities within the boundaries of the "checkerboarded" reservation and offers a forum for resolving potential conflicts. The process,…

Lenor Scheffler: The Lower Sioux Indian Community's Approach to Citizenship

Lawyer Lenor Scheffler (Lower Sioux Indian Community) provides an overview of the Lower Sioux Indian Community's approach to defining citizenship, which is predicated on residency within the Lower Sioux reservation's boundaries. She also discusses how eligibility for tribal social services is tied…

Sarah Deer: The Muscogee (Creek) Nation's Approach to Citizenship

Sarah Deer (Muscogee), Co-Director of the Indian Law Program at the William Mitchell College of Law, provides a brief overview of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation's unique approach to defining its citizenship criteria, which essentially creates two classes of citizens: those who run for elected office,…

Bethany Berger: Citizenship: Culture, Language and Law

University of Connecticut Law Professor Bethany Berger provides a brief history of the federal policies that have negatively impacted the ways that Native nations define and enforce their criteria for citizenship historically through to the present day. This video resource is featured on the…

John Petoskey: The Central Role of Justice Systems in Native Nation Building

John Petoskey, citizen and longtime general counsel of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians (GTB), discusses the key role that justice systems play in Native nation building, and provides an overview of how GTB's distinct history led it to develop a new constitution and system of…

Jill Doerfler: Constitutional Reform at the White Earth Nation

In this in-depth interview with NNI's Ian Record, Anishinaabe scholar Jill Doerfler discusses the White Earth Nation's current constitutional reform effort, and specifically the extensive debate that White Earth constitutional delegates engaged in regarding changing the criteria for White Earth…

Honoring Nations: Pat Cornelius: Oneida Nation Farms

Manager of the Oneida Nation Farms Pat Cornelius presents an overview of the organization's work to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

Robert McDonald: Engaging the Nation's Citizens and Effecting Change: The Salish and Kootenai Story

Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) Communications Director Robert McDonald discusses the challenges his nation faces when it comes to effectively educating and engaging its citizens -- particularly in the age of social media -- and what the nation is starting to do about it. He…

Robert A. Williams, Jr.: Law and Sovereignty: Putting Tribal Powers to Work

University of Arizona Professor of Law Robert A. Williams, Jr. provides an overview of the U.S. government's centuries-long assault on tribal sovereignty -- in particular the ability of Native nations to make and enforce law -- and stresses the importance of Native nations systematically building…

Priscilla Iba: Osage Government Reform

Osage Government Reform Commission Member Priscilla Iba discusses the historical factors that prompted the Osage Nation to create an entirely new constitution and governance system, and how the Nation went to great lengths to cultivate the participation and ownership of Osage citizens in the…

Osage Nation to receive $7.4 million in Cobell Land Buy-Back program

The Land Buy-Back Program for Tribal Nations has come to the Osage and the federal government is proposing $7.4 million to buy back fractionated land interest from individual tribal members. According to tribal development and land acquisition director Bruce Cass, who is working with Osage attorney…

Collectively Managing Allotment Lands Is Better

Indian allotment holders are not making enough money from their allotments. One way for tribal allotment holders to gain more economic income from their allotments is to organize a corporation under tribal law and collectively manage allotted lands in order to gain more income for allotment holders…

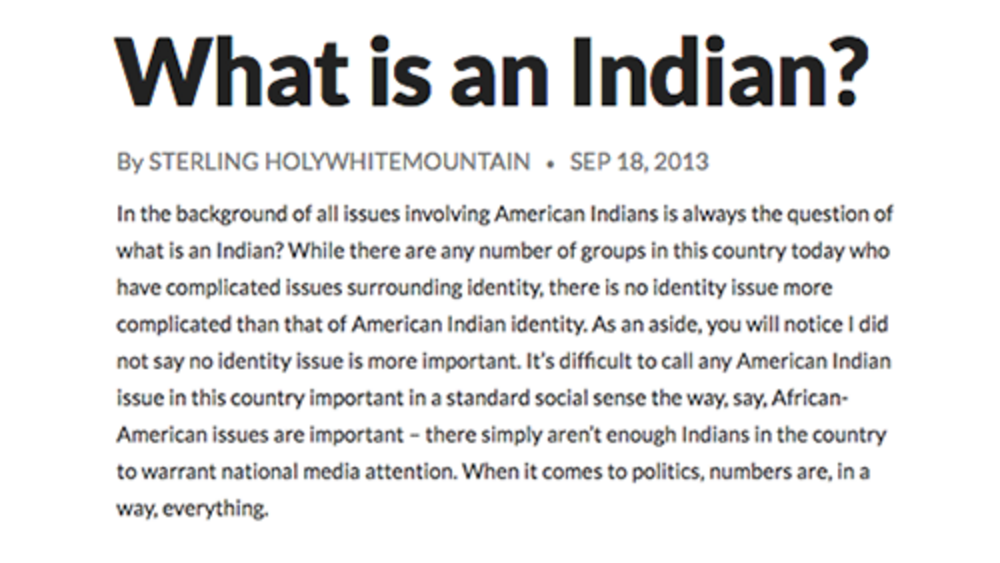

What is an Indian?

In the background of all issues involving American Indians is always the question of what is an Indian? While there are any number of groups in this country today who have complicated issues surrounding identity, there is no identity issue more complicated than that of American Indian identity. As…

Indian Pride: Episode 108: Economic Development

This episode of the "Indian Pride" television series, aired in 2007, explores the economic development efforts of selected Native nations cross Indian Country. It also features an interview with Lance Morgan, CEO of the Winnebago Trib'es Ho-Chunk, Inc., who provides an overview of the evolution of…

Vine Deloria's Last Video Interview

American Indian author, theologian, historian, and activist Vine Deloria, Jr. (1933-2005) talks with documentary film producer Grant Crowell about traditional Indigenous governance systems and criteria for citizenship, the impact of colonial policies on tribal citizenship (specifically the effects…

Why Treaties Matter: Video Gallery

This video gallery serves as a companion piece to "Why Treaties Matter - Self Government in the Dakota and Ojibwe Nations," a travelling exhibit on treaties between Dakota and Ojibwe people and the U.S. It features testimonies from Native nation leaders and citizens about many of the exhibit's main…

Native Report: The Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians and the City of Palm Springs

This episode of Native Report examines the unique relationship between the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians and the City of Palm Springs, California, casting much-needed light on the benefits of intergovernmental cooperation. (Segment placement: 1:17 - 8:44)