Indigenous Governance Database

civic responsibilities

Indigenized Communication During COVID-19

During times of crisis, the messages we send to our stakeholders matter more than ever. Tribal governments and Native organizations are on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic and are making important decisions to protect the health and safety of their people. As Indigenous people, we…

Robert Innes: Elder Brother and the Law of the People: Maintaining Sovereignty Through Identity and Culture

Robert Innes, a citizen of the Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan, discusses how traditional Cowessess kinship systems and practices continue to structure and inform the individual and collective identities of Cowessess people today, and how those traditional systems and practices are serving…

Richard Luarkie: The Pueblo of Laguna: A Constitutional History

In this informative interview with NNI's Ian Record, Laguna Governor Richard Luarkie provides a detailed overview of what prompted the Pueblo of Laguna to first develop a written constitution in 1908, and what led it to amend the constitution on numerous occasions in the century since. He also…

Shannon Douma: Cultivating Good Leadership: The Santa Fe Indian School's Summer Policy Academy

Shannon Douma (Pueblo of Laguna) provides a detailed overview of how the Santa Fe Indian School's Summer Policy Academy works to develop Pueblo youth to ably take the leadership reins of their nations through a rigorous curriculum designed to build up their sense of cultural identity and personal…

Shannon Douma and Richard Luarkie: How Do We Choose Our Leaders and Maintain Quality Leadership? (Q&A)

Shannon Douma and Richard Luarkie (Pueblo of Laguna) field questions from seminar participants about how the Pueblo and also the Santa Fe Indian School's Summer Policy Academy groom Pueblo youth to take over the reins of leadership of their nations.

Carlos Hisa and Esequiel (Zeke) Garcia: Ysleta del Sur Pueblo: Redefining Citizenship (Q&A)

Carlos Hisa and Zeke Garcia from Ysleta del Sur Pueblo (YDSP) field questions about YDSP's current community-based effort to redefine its criteria for citizenship, and they provide additional detail about the great lengths to which YDSP has gone in order to document the origins and history of their…

Richard Luarkie: How Do We Choose Our Leaders and Maintain Quality Leadership?: The Pueblo of Laguna

Pueblo of Laguna Governor Richard Luarkie provides a brief overview of how Laguna citizens gradually and systematically ascend up the leadership ranks within the Pueblo through their adherence to and practice of Pueblo core values.

Carlos Hisa and Esequiel (Zeke) Garcia: Ysleta del Sur Pueblo: Redefining Citizenship

Carlos Hisa and Esequiel (Zeke) Garcia from Ysleta del Sur Pueblo (YDSP) provide an overview of the approach that YDSP is following as it works to redefine its criteria for citizenship through community-based decision-making. They also share the negative impacts that adherence to blood quantum as…

Luann Leonard, Stephen Roe Lewis and Walter Phelps: Bridging the Gap: How Native Culture Forges Native Leaders

Luann Leonard (Hopi), Stephen Roe Lewis (Gila River Indian Community), and Walter Phelps (Navajo) discuss how their personal approaches to leadership have been and continue to be informed by their Native nations' distinct cultures and core values and those keepers of the culture in their…

Native Leaders and Scholars: Citizens Versus Members: Some Food for Thought

Native Leaders and scholars discuss the pervasive role that terminology plays in conceptions of Native nation sovereignty and citizenship, comparing and contrasting the terms "member" and "citizen" and discussing the origins of the term "member" in Native nations' definitions of who is to be…

Chris Hall: Cultivating Constitutional Change at Crow Creek

Native Nations Institute's Ian Record conducted an informative interview with Chris Hall, a citizen of the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe and a member of Cohort 4 of the Bush Foundation's Native Nation Rebuilders program. Hall discusses Crow Creek's current effort to reform its constitution and the…

Angela Wesley: A "Made in Huu-ay-aht" Constitution

Angela Wesley, Chair of the Huu-ay-aht Constitution Committee, discusses the process that the Huu-ay-Aht First Nations followed in developing their own constitution and system of government. She describes how Huu-ay-aht's new governance system is fundamentally different from their old Indian Act…

Herminia Frias: Engaging the Nation's Citizens and Effecting Change

Herminia Frias, former Chairwoman of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe, discusses the citizen engagement challenges she encountered when she took office as an elected leader of her nation, and shares some effective strategies that she used to engage her constituents and mobilize their participation in and…

Honoring Nations: Joyce Wells: Project Falvmmichi

Choctaw Nation Healthy Lifestyles Program Director Joyce Wells describes how a 16-year-old Choctaw citizen transformed her idea and passion into a comprehensive education and mentoring program that seeks to prevent domestic violence in Choctaw communities.

Native Nation Building TV: "Leadership and Strategic Thinking"

Guests Peterson Zah and Angela Russell tie together the themes discussed in the previous segments into a conversation about how Native nations and their leaders move themselves and their peoples towards nation building. They address the question all Native nations have: How do we get where we want…

Empowering Parents Brings Community Change in Wind River

If you are a parent who has ever thought, “What can I do?” or “I am just a parent,” Clarisse Harris, Northern Paiute, has a program that might interest you. On the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, the Parent Leadership Training Institute is arming parents with the tools to bring changes within…

Cheyenne River Youth Project Turns 25, Launches Endowment and Keya Cafe Featuring Homegrown Food

Twenty-five years ago, Julie Garreau (Cheyenne River Lakota) developed the Cheyenne River Youth Project (CRYP) from a converted bar on Main Street in the tribe's capital Eagle Butte, South Dakota. For 12 years she volunteered her time to get an after-school program off the ground...

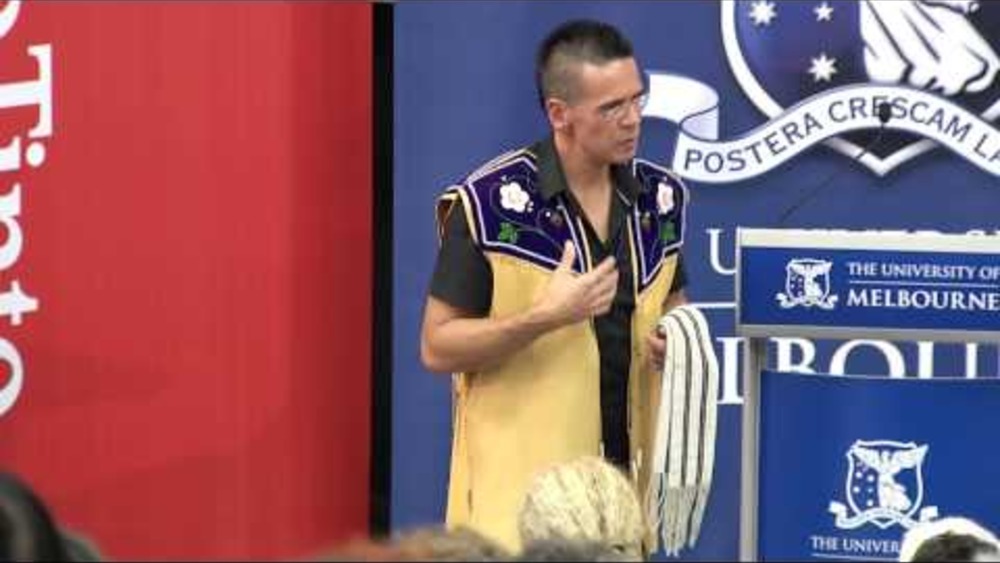

The 2013 Narrm Oration: Taiaiake Alfred

The 2013 Narrm Oration, "Being and becoming Indigenous: Resurgence against contemporary colonialism", was delivered by Professor Taiaiake Alfred on 28 November. Professor Alfred is the founding Director of the Indigenous Governance Program at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada…

The Ways: Living Language: Menominee Language Revitalization

Before European contact, the Menominee Indian Tribe had a land base of over 10 million acres (in what is now known as Wisconsin and parts of Michigan) and over 2,000 people spoke their language. Today, their land has been reduced to 235,000 acres, due to a series of treaties that eroded the tribe’s…